Today is my mother’s birthday, and although she died thirty years ago, she lives on in this writer’s genetic code. For example, whenever I misplace my car keys, only to find them in the most obvious of places, a voice inside my head will announce, “If it’d been a snake, it would’ve bit me.”

Cora Irene Morton was born in Eureka, Utah—a hardscrabble mining camp where I presume residential snakebites were commonplace. She was the youngest of five siblings, not counting Little Wesley, who died of the croup at the age of two. It was in Eureka where she learned handwriting—the Palmer method from which she never deviated. That’s her, with the freckles and braids, seated in the front row.

When she was 12, her father John Wesley died of pneumonia silicosis—the result of inhaling rock dust in the mines of Eureka. “Leaded,” as my mother put it. But before falling sick he had relocated to Provo, situated in Utah’s fertile crescent where fruit trees and berry patches could flourish. Sadly, he didn’t live to enjoy the fruits of his underground labor.

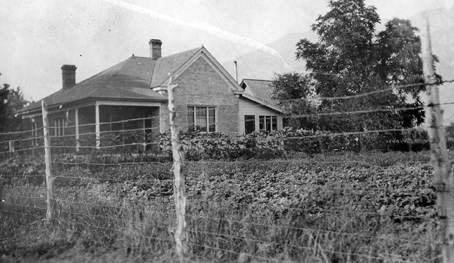

Directly across Fifth West from the Morton house stood a brick bungalow that my paternal grandfather had bought, having worked his way up from the equally deadly coal mines of Carbon County. James Menzies sired four daughters and one son, Charles—known to his boyhood chums as “Chick.” Cora, whose girlhood nickname was “Squeaky,” fell head over heels for the boy across the street, and that’s how I came into the world.

I was born in Salt Lake City, but I didn’t grow up here. In 1945 my family moved to Price, in the heart of coal mining country. There I spent an idyllic boyhood exploring the surrounding foothills with my dog Elmer at my side, Daisy air rifle in hand should we encounter one of those ever-present snakes. And it’s in Price that my parents lie buried in Cliffview Cemetery, surrounded by friends and neighbors, including members of what my mother called “The Club.”

Once a month, The Club would convene at a member’s house, at which times husbands would be sent packing and children banished to the basement. Huddled beneath the floorboards, I’d hear the tinkling of teacups, the clicking of high heels, spontaneous eruptions of feminine laughter–including the distinctive giggle that had earned Mom her girlhood nickname.

Now and again, my parents would reminisce about growing up in Provo—back before the apple orchards and berry farms had become subdivisions. However, the Menzies house, with its deep, irrigated yard was still standing, as was the Morton house across the street. Long vacant, it was slated to be razed in order to make room for the Utah Valley Hospital. One day, Mom took me on a guided tour of the property, where rows upon rows of green beans and snap peas once grew. But now it was all weeds; that is, except for a concrete walkway John Wesley had poured on April 30, 1922. While it was still wet, he had scratched in the name of his beloved daughter Cora. “Is it possible we could find it?” I wondered.

“Well, it’s right there,” said Mom, pointing downward. And so it was. Had it been a snake, it surely would have bit me.