BORDERLANDS

I must be the only person in America who doesn’t carry a smart phone. Why? Because I believe that when you go somewhere, you shouldn’t stay in constant contact with those you left behind. Wherever in the world you are at any given moment, that’s where you should be. You should be looking around, not gazing at some little digital display in the palm of your hand.

That said, today I find myself wishing I had a smart phone, one with a GPS app that would show me the way to Clark Hunt’s house in Sierra Vista. Road signs are no help at all.

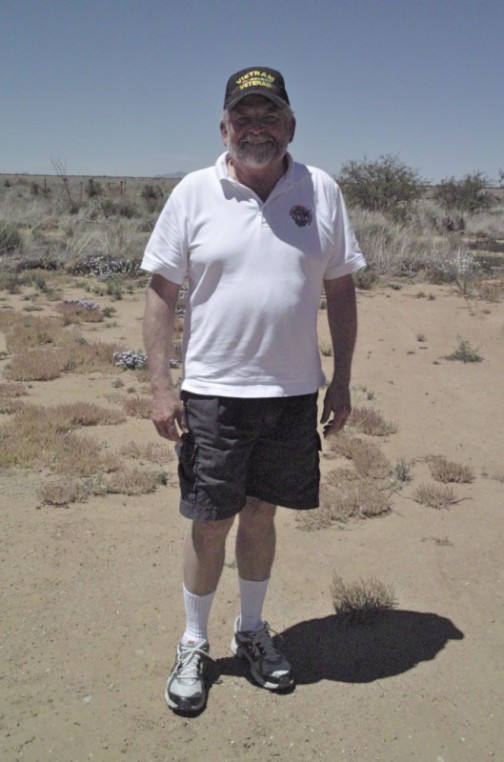

Turns out Clark doesn’t live on a street named after him. He lives on Via Vaquero, a dirt lane that branches off another dirt lane named Rancho Pequenos. There, in the middle of the Sonoran desert I see him waving. For someone who recently turned 70, he looks to be in good shape. I notice that he’s wearing a Vietnam Veteran cap, which entitles him to a ten percent discount at all fast food restaurants in the region. Meantime I, who successfully avoided serving in the military, pay full price, and no one ever thanks me for my service. Had I known back then what I know now, would I have done things differently? Who knows? In the late Nineteen Sixties, the two of us were confronted with a hard choice: Stay in college forever, or drop out and be drafted? Turns out neither of us had the wherewithal to attend graduate school. Instead of waiting to be drafted, Clark enlisted in the Army and rose to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. He and his wife Caroline have traveled the world over and are planning a trip this summer to Europe, where they will attend an Andre Rieu concert.

Andre Rieu? In 1968 my favorite band was Country Joe and the Fish.

“Well, come on all of you big strong men, Uncle Sam needs your help again,

He got himself in a terrible jam, way down yonder in Vietnam.

Put down your books and pick up a gun,

We’re gonna have a whole lotta fun.

CHORUS

And its 1,2,3 what are we fightin’ for?

Don’t ask me i don’t give a dam, the next stop is Vietnam,

And its 5,6,7 open up the pearly gates.

There ain’t no time to wonder why…WHOPEE we’re all gonna die.”

I managed to evade military service by flunking a pre-induction exam—or acing, it, depending upon your viewpoint. Doesn’t matter. The main thing is, I didn’t go to ‘Nam, and I didn’t come home in a box. My only regret now is that I’m obliged to pay full price for chicken fries at Burger King.

For the next two hours the hawk and dove sit together on the veranda, sipping wine, reminiscing, and watching songbirds at the feeder. We both have traveled far from where we started out, albeit along separate paths, and I’m pleased to report we remain good friends. Too bad our mutual boyhood pal and fellow tire recapping drudge, Captain Clive Jeffs, who punched out of his jet over Vietnam in 1971 and hasn’t been seen or heard from since, couldn’t be with us.

As long as I’m in the area, I decide to drop in on an old mentor and scold, William Childress. Childress, who is 82, relocated from Folsom, California, to Douglas, Arizona, about a year ago, following his wife’s untimely death from cancer. Of his half dozen or so wives, Diane was his favorite, and her passing laid him low. In fact, after he went missing, I was beginning to fear the worst. But lo and behold! There he is, standing in front of his little blue house just off King’s Highway, looking just as feisty as ever.

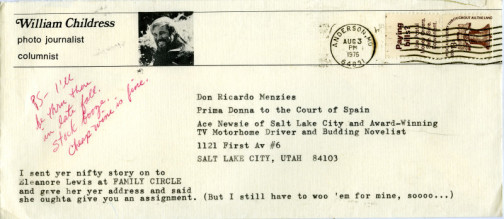

William Childress is a lifelong freelance journalist who has sold thousands of articles—more magazine sales, I’m guessing, than any writer alive. OUT OF THE OZARKS, a collection of essays he wrote for the St. Louis Post Dispatch while living in a trailer in Anderson, Missouri, is one of my all-time favorite reads. He also writes poetry; however, whenever I suggest that he is “sensitive,” he immediately stiffens and reverts to paratrooper mode. (“Sensitive,” by the way, is the diagnosis that disqualified me for military service.)

Back in the Seventies, I’d get regular letters from Childress, tucked inside envelopes covered with postscripts and afterthoughts. His pet accusation then was that I’m a “prima donna”—this in spite of my Frank McCourtlike upbringing. According to him, I’ve had it much too easy. The son of itinerant sharecroppers, Childress picked cotton as a lad and enlisted in the Army in hopes of scoring three hots and a cot. As a veteran of the Korean conflict, he, too, is entitled to a ten percent discount on chicken fries at Burger King.

Toward evening, we swing by a screened-in tavern that looks to be a cross between Rosa’s Cantina and Sam the Lion’s pool hall. There we are joined by an assortment of central casting-worthy roustabouts and cowboys. We are served pitcher after pitcher of beer by a rail-thin, barkeep/proprietor with a husky voice and leathery complexion. Everyone smokes but nobody swears. The willowy, nut-brown proprietor has a rule against use of the F-word, which renders the taller of the two cowboys at our table all but speechless. The ex-con named Chevy isn’t even allowed to step inside.

Later, I roll out my sleeping bag on an inflatable mattress just outside Chilly’s little blue house. The stars overhead shine brightly; in the distance I hear the yip, yip, yip of coyotes, followed by the woof, woof, woof of guard dogs. In the predawn, the yipping and woofing subside and through the wall I can hear my host talking to himself as he sits at his computer keyboard, earnestly humming away on his latest project, an homage to his beloved Diane.

Come sunup, the two of us eat breakfast at the venerable Gadsden Hotel in the border town of Douglas. Ever the optimist, Chilly asks our adorable waitress, who looks to be about 17, if perchance she has a twin sister 60 years her senior. Which leads me to wonder whether the pills Chilly takes to forestall Alzheimer’s might not be working. Or perhaps the Cialis is kicking in?

Checking the map, I see that I’m only half a mile from the Mexican border. In 1968, I crossed that border and continued southward, all the way to Mazatlan. The difference between then and now is that today have a home to return to, and someone there who will notice if I never do. So I climb aboard my bug-splattered Bavarian beast, wave goodbye to Chilly and set off. At a place called Pirtleville, I turn off highway 80 onto 191. My trip odometer reads 999.9 miles. Then zeroes. I’m on my way home.