Come Thursday Morning, I won’t bother to venture out into the cold, predawn darkness in search of the morning’s newspaper, for it won’t be there, its absence heralding the end of a 150-year-old tradition known as The Salt Lake Tribune. Oh, sure, we’re told local news can still be accessed via a computer screen, but to those of us who came of age in the Nineteen Fifties, things will never be the same.

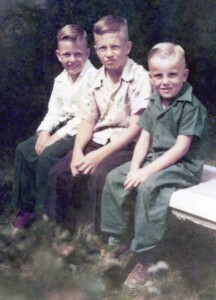

What I remember about Thursday’s paper in those days is that was heavy with advertising copy—same as Utah’s afternoon daily, The Deseret News, which for nine long years was a burden borne by the three Menzies brothers, each of us born three years apart and each of us serving a three-year term as delivery boy. Should an issue ever go missing, it was my poor mother who fielded the customer’s complaint–and, believe me, she wasn’t one to make excuses for her sons.

It wasn’t as if I ever wanted to be a paperboy; it was just another hand-me-down. Ditto the canvas bag and balloon-tired, one-speed Schwinn bicycle astride which we couriers made the swift completion of our appointed rounds.

Then there was the Baby Ben alarm clock. How hateful its bedside clanging on a predawn Sunday, which was the one day of the week when Deseret News carriers were tasked with delivering the morning Tribune. No matter how cold out, or how wet, you still had to saddle up the old Schwinn. No paperboy ever awoke a parent to ask for a ride—not in my family, anyway.

I’d peddle south five city blocks to the paper stop, which was an empty lot where bundles were dropped from a Wycoff truck that had miraculously survived the treacherous crossing of Soldier Summit and twisting descent into Price Canyon. There, you would find a handful of Dickensian figures warming their mittened fingers over a blazing fire kindled by advertising inserts. You had to show up early, or else one of those shady characters would have seized the opportunity to slip a few issues from your bundle, which would leave you short-handed. One morning I arrived late to discover I was an astonishing 25 newspapers short! I detoured downtown in hopes of raiding a coin-operated stand in front of Kelley’s Drug Store, only to discover it had been emptied. Desperate, I lay in wait outside the entrance of a sub-contractor known as Arrow Auto Lines, which distributed newspapers from Price to various outlying mining camps. I watched as the driver set a bundle of newspapers on the tailgate of his station wagon; then, as he re-entered the garage, peddled past and disappeared around a corner, bundle in hand. Too bad for subscribers in Hiawatha and Wattis, but good news for my customers and also good news for my mother, whose switchboard wouldn’t be lighting up later.

WHY were there never enough issues to go around? Well, in those days paperboys were independent businessmen—retailers, I suppose you might say. We were provided newspapers at a discount and sold them for slightly more. Each month, we’d be presented a bill for issues received, and each month we’d make the rounds of customers in order to collect. The difference between what we were charged and what we collected was our theoretical profit. I say “theoretical,” because if only half a dozen customers failed to pay up, you made nothing. So, the only way to clear a profit as a carrier was to purchase fewer newspapers than you had customers, and then get to the paper stop early in order to pad your bag with issues purloined from the bundles of others. In other words, it was a dog-eat-dog operation, and in order to survive, you had to be crafty and willing to play dirty when necessary. Which is why, following my three years of indentured servitude, I didn’t hand the family route down to my kid sister, who went on to become a proper young lady of impeccable character who never gave her mother a moment’s grief.