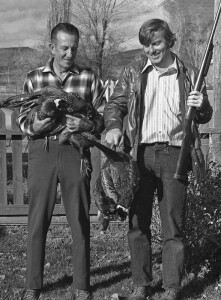

Let me begin by saying I’ve always enjoyed hunting—in particular, with my beloved father. Pheasant season was the best, and I distinctly remember dropping a bird the first time I pulled the trigger on the hand-me-down Iver Johnson 16-gauge single shotgun that my father had packed before he inherited his father’s 12-gauge Remington pump. Thinking back, it was generous of Dad to hold his fire until after I’d taken my shot. But, then, it didn’t really matter which of us killed the bird, or even if the bird got away. The main thing was just spending time together.

In between pheasant seasons, I’d roam the fields and foothills alone, always with a firearm of some kind in my hands—first, a Daisy air rifle, then a Crossman pellet gun, and finally a .22. I did so because in the place where I grew up, a kid wandering the hills by himself without a firearm in his hands would have been a cause for concern—if not alarm.

I loved shooting; however, on those rare occasions when I managed to hit something, I was filled with remorse. Why had I killed something just to leave it lying there? Hunting for supper was okay, but wasting game wasn’t cool. That’s when I decided to lay down my arms and now roam the hills with a camera. It’s a big sucker, heavier than any rifle or shotgun I ever carried, and I have to get pretty close to my prey in order to squeeze off a good shot. If I’m lucky, the creature in my viewfinder will realize it’s a camera I’m toting and not a gun, and will oblige with a nice pose before bounding off.

Now, if I had shot that lovely pronghorn with a rifle instead of a camera, I’d have had a big mess on my hands. I’d have to gut it, tag and bag it, drag it home and skin it the same way my father used to skin the dead deer he’d brought home lashed to the front fender of his 1950 Mercury. Then he’d cut it up and deliver the various cuts to my mother, whose job it was to somehow remove the gaminess from wild venison. I’m told that antelope meat is even more problematic. The only salvageable part would probably be the head, which I could take to a taxidermist who would craft a fiberglass facsimile of same, suitable for hanging above the fireplace, from which perch it could glower reproachfully through glass eyes at its murderer. Sounds fun? I don’t think so!

On yesterday’s “Outdoors With Adam Eakle” broadcast there appeared a snapshot of the week entry that featured a 16-year-old girl standing over the corpse of a bull moose she’d shot. “A memory to last a lifetime!” exulted the host. I totally agree. That glassy gaze from above the mantel will forever be a grim reminder of the time she’d callously ended the life of a stationary ungulate with a high-powered scoped rifle. Degree of difficulty: zero.

Why, just the other day I had a chance to shoot not just one but two bison, which wasn’t easy. First, I had to exit my comfortable car and wrestle that big 550mm Nikon lens into position, then wait until the animals came into range. Lastly, at just the decisive moment I pressed the shutter button. Click! I’d gotten them both with one shot, and I don’t think either of them ever felt a thing.