I was halfway through developing a roll of Tri-X the morning the phone rang. It was my mother, her voice trembling. A policeman was in the house, a terrible accident had occured. Charles, her husband of fifty years was dead, his pickup truck having inexplicably veered off airport road into a power pole as he was returning from a trip to the city dump.

As I listened, I continued to agitate the film tank at thirty-second intervals because that was what I’d taught myself to do. Thus, the negatives survive—pictures I’d taken of my son Alex, who was two years old at the time.

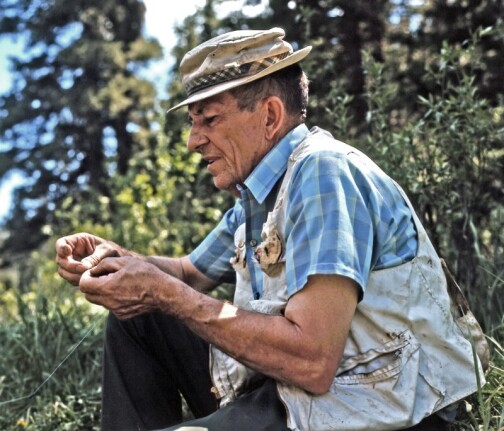

That was thirty-five years ago. Alex is now a devoted father to his own two-year-old, and remembers nothing of the grandfather who loved him so, same as my lovely granddaughter will most likely have to be told just who is that grizzled geezer in the family photo album.

At what point do our forebears become real to us, or are we all just destined to fade into oblivion? As a photographer, I struggle to hold on—but, alas, I can’t halt the relentless march of time. However much we might wish otherwise, pictures will not bring back the dead.

I suppose my big mistake was waiting until I was forty years old before siring a son. My own father, like most men of his generation, got started sooner, and he had more than just one kid. As the chief breadwinner, he had to go to work every day, so he didn’t have the luxury of being a stay-at-home dad like me, or a forced-to-work-from-home father like my son. So I only saw him long enough to wave goodbye as he left for work in the morning, and then when he returned I’d run down the sidewalk to greet him. I remember he always smelled of sawdust.

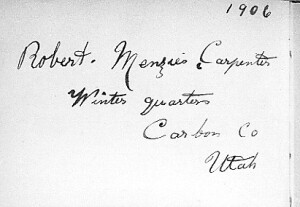

After Dad was killed, Mom went crazy and everything went straight to hell. What my demented mother didn’t throw away was carted off by opportunistic neighbors; however, Dad’s workbench was too heavy to steal and thus ended up in my possession, along with many of his woodworking tools, some of which date back to my great-grandfather Robert, who worked as a carpenter in the vanished coal camp of Winter Quarters.

Winter Quarters was a suburb of Clear Creek, which in turn was a suburb of Scofield, which is a very long ways from great-grandad’s birthplace of Glasgow. Still, the aspens that grow in the high country of Utah’s Wasatch Plateau do somewhat resemble the larches of Scotland, and I suppose that’s why I feel vaguely at home there. To my father, it was also a special place, and I’m grateful that he and I were able to spend quality time together fishing Scofield reservoir and Huntington Creek, and which is why I go there whenever I can, not to fish but to think back on a happier time when I had someone special to telephone on Father’s Day