So, I’ve been spending some time in my darkroom, which I would describe as state-of-the-art, circa 1985. Pretty much all the photo processing tools I have are even older than that—the older the better, when it comes to such things as enlargers, easels, trays and hard rubber developing tanks. Stuff that used to cost a fortune can now be had for pennies, thanks to the digital revolution that rendered traditional analog photography obsolete.

Today I was thinking back to the nineteen fifties, when my darkroom occupied a corner of the basement bedroom I shared with my two older brothers. During the daytime it was a bitch trying to achieve total darkness, and in fact I never succeeded. Happily, film and paper in those days weren’t overly sensitive to light, and one paper in particular appeared to be all but impervious to exposure. It was called Athena, and was manufactured by Eastman Kodak.

Where I lived, it wasn’t easy to get one’s hands on a package of enlarging paper. My friend Barney DeVietti, proprietor of Barney’s Photo Shop, usually kept a package of Medalist or a box of Velox on hand for me—his only customer—but on occasion even he ran out of stock. That’s when I would turn to the only other supplier in town, an establishment called Flossie’s Dress Shop. Although Flossie’s main stock in trade was women’s wear, she also dabbled in watch repair and photographic paper. Where it came from, nobody knew. I’m guessing that she and/or her husband dabbled in photography in their off hours.

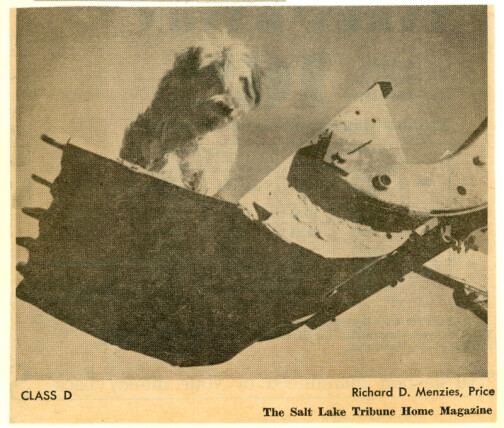

Her selection was meager, consisting of a single package of Kodak Athena—a paper I’d never heard of before or since. My first attempts to expose the stuff all came out blank, and I began to wonder if perhaps I was inserting the paper into the easel upside down. So I gave it the old tongue test, which confirmed which side was the sticky—i.e., emulsion side. I tried longer and longer exposures, until at last a very faint image began to register. So faint that I calculated a proper exposure would be somewhere in the vicinity of forty-five minutes.

I wasn’t about to just sit there in the semi-darkness for forty-five minutes, and so slipped out the door and went for a bicycle ride. Upon returning, I switched off the smoking enlarger and slipped the paper into the developing tray. Voila! An image appeared. It was a picture of a dog sitting in a tractor scoop that I’d shot using 828 Verichrome Pan—a format and film that have long since gone the way of the dinosaurs.

I didn’t bother to make a second print because the entry deadline for the Salt Lake Tribune’s weekly snapshot contest was fast approaching. I dropped my entry in the mailbox, and what do you know? My picture was a winner, and I pocketed five bucks for my effort.

I don’t remember ever making another enlargement on Kodak Athena paper, which I now suspect wasn’t even an enlarging paper. Most likely it was something you’d put into a contact frame and expose by direct sunlight. In other words, it was really old—even by my standards.

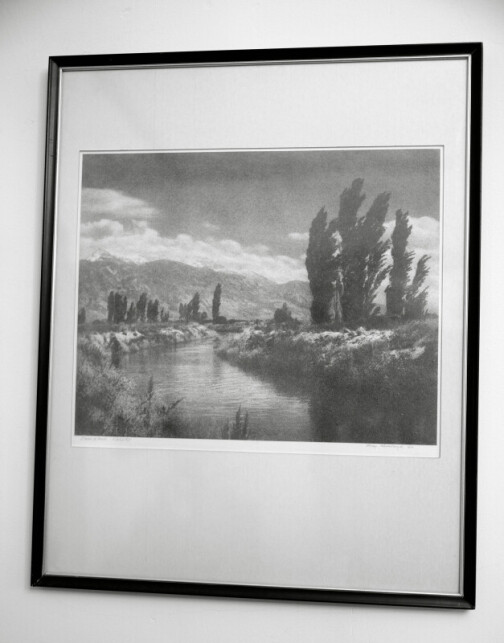

I never bought another package of photographic paper from Flossie, whose shop eventually closed for want of customers. However, as luck would have it, our paths crossed decades later, as I was helping a friend of mine install a gas furnace in a house on Michigan Avenue in Salt Lake City—a house that was occupied by none other than Flossie! We chatted a bit, and I learned that she and her late husband were indeed avid amateur photographers in the olden days. Looking around, I spotted a framed photograph on the wall.

“That’s a nice bromoil,” I said.

“You’re the only person who would know it’s a bromoil,” said Flossie. “Take it; it’s yours.”

And so now it hangs on my wall, and I like it. It’s titled “Peaceful Valley” and signed by Ray Kirkland of Bountiful, Utah. Recently, I took it out of its frame and learned that it was awarded a gold medal at the 1962 Photography Society of America convention in San Francisco. Well done, Ray! And thanks again, Flossie, wherever you are.