Were she still alive, today would be my mother’s 106th birthday, but of course, no one in her family ever lived that long. Given the fact she was born in the hardscrabble mining camp of Eureka, Utah, it’s a miracle she survived childhood.

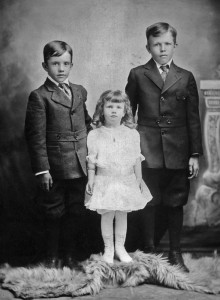

Cora Irene Morton was the youngest of six children and the apple of her father’s eye. Sadly, John Wesley Morton died when Cora was just twelve—of respiratory failure, the result of ingesting carcinogenic rock dust underground. Before dying, however, he had successfully worked his way up to ground level and had relocated his family from a clapboard shack in Eureka to a brick house on Fifth West Street in verdant Provo. Directly across the street stood the home of James W. Menzies, who had worked his way out of the coal mines of Carbon County. Auto traffic on Fifth West in those days was nothing like it is today; hence, my father Charles was able to safely cross the street, and the rest is history.

Before it was razed to make way for the Utah Valley Hospital, I shot this picture of my parents standing in front of the derelict Morton house, where as a boy I spent very little time because my family didn’t live in Provo. Once, I remember I was collecting grasshoppers in my grandmother’s weedy front lawn when a local kid pulled up on his bicycle.

“ If I were you,” he warned, “I wouldn’t play here. The lady who lives in that house is the meanest person in Provo.”

Fact is, Grandma Morton wasn’t mean—she’d just had a hard life. Widowed and crippled from a stroke, it was all she could do to keep snap beans on the table. I’m assuming she relied on her older children for financial help; as for Cora, there was never a possibility of attending college. Instead, she was groomed to become a wife and homemaker.

Mom took her domestic responsibilities seriously. Cooking, cleaning, scrubbing, ironing, gardening—you name it, she was on it. Our house, however humble, was always squeaky clean. My favorite spot, whenever it was available, was on a stool in the kitchen where I’d watch as Mom toiled over a hot stove. Which was good training for the son who, even though he went to college, was never able to find a good-paying job. At least I know how to make a béchamel sauce!

Later in life, after the last of her four kids had flown the nest, Mom’s culinary skills landed her a job as a school lunch lady, where for the first time in her life she enjoyed the company of co-workers. Those were happy years, and how I wish they could have gone on longer. Unfortunately, somewhere in our Morton genes lurks a propensity toward dementia, and by the time my mother was my age, she had pretty much lost her mind. Believe me when I say that Alzheimer’s disease is worse than death, because it robs a person of everything that makes life worth living. Memory, yes—but also the capacity to recognize or feel affection toward one’s spouse, children, grandchildren, neighbors and friends. Thus, toward the end, my mother had become the meanest person in town, and it has taken me many years to remember her otherwise. Honestly, I’m grateful that she didn’t live a day longer than she did, and if there is a heaven, I’m hoping her eternal spirit is that of a young woman, beautiful, madly in love with the boy next door and eagerly looking forward to a future as the mother of his children.