My father has been gone now for 34 years, during which time the house we proudly called home for fifty years has become a dump. Longtime neighbors have also passed on, their homes now occupied by strangers. In the little town where I grew up I recognize no familiar faces—not even at high school class reunions.

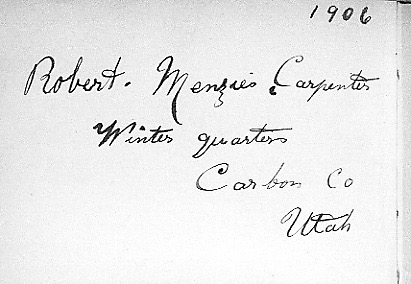

So, what’s left? Well, what remains is the landscape of my youth, including the Wasatch Plateau, home of verdant alpine valleys dotted with aspen groves not unlike the larches surrounding Castle Menzies in Weems. The Plateau, however, features no castles—just faded mining camps such as Winter Quarters, where at the turn of the century a Scottish immigrant named Robert Menzies once labored as a carpenter. All that remains of Robert’s life story is a single book: PRACTICAL USES OF THE STEEL SQUARE, on the flyleaf of which my great-grandfather inscribed his name. In addition to the book, I’m in possession of Robert’s steel square, with which a skilled carpenter can calculate all the angles necessary to build a staircase or frame a roof. My father, himself a skilled carpenter, once tried to show me how to use it; however, my brain is evidently impervious to practical input.

When I was a kid I used to run out the door to greet my father when he returned from work, packing a lunch pail and smelling of sawdust. As I grew older, alas, our relationship cooled a bit—this after word got around that I was intent on becoming a writer. My hard working father equated writing with sloth, and of course he was mostly right. It was only later, after he retired and discovered for himself the pleasures of unstructured time that he and I became really close.

Our favorite pastime was fishing and our favorite fishing spot was Huntington Creek. Sometimes we caught fish; sometimes we didn’t—but what did it matter? The important thing was spending time together in a part of the world that was the setting of my father’s own growing-up years. As a toddler, he’d experienced epic snowfalls in Winter Quarters. As a teenager, he’d peddled produce to the coal miners of Pleasant Valley from his Uncle Lou’s horse-drawn wagon. As an adult, he’d conducted repairs on Scofield’s elementary school. On such jobs I’d tag along, even though as a helpmate I was of no help whatsoever. Mostly, I just poked among the ruins–tumbledown mining buildings I presume my great-grandfather had helped erect, using his practical steel square.

After Dad retired I finally became useful as his leisure-time consultant. Because I had no regular job, I was available whenever my father needed a fishing companion. I even introduced him to the joys of picking up empty beer cans alongside State Route 31. Aluminum gold! But of course it wasn’t about the money; fact is, the good life is never about the money. The good life is whatever time you spent with your father when he was alive that’s worth remembering.