Multiple bodies are spinning in their graves this morning, following news that a real estate developer has plans to turn the historic Homestead Resort in Midway into a gated, upscale, exclusive luxury housing development. Though not yet dead, I find myself turning circles in my Herman Miller Aeron chair.

The Homestead dates back to 1886, when it was known as Schneitter’s Hot Pots, founded by Swiss immigrant Simon Schneitter. There, bathers wearing one-piece swimsuits floated about, clinging to buoyant board in geothermally-heated water drawn from the valley’s tallest fumarole. By and by a second pool was added, fed by a proprietary mountain spring, so that guests had a choice between being parboiled or frozen. At the time I started work there in the summer of 1967, the 50-acre resort offered overnight lodging, fine dining in the main dining hall and casual dining in the thematically-decorated Gay Nineties Bar, what we on staff mocked as a hangout for homosexual nonagenarians.

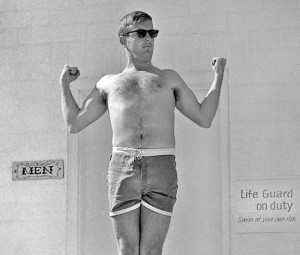

Ferron and Martha Whitaker owned the place, while Ferron’s brother Berlin “Uncle Buddy” Whitaker supervised the aquatic center. Uncle Buddy was also in charge of painting signs, my favorite being NO SMOKING EXCEPT IN GRASS AREA. As head lifeguard, it was my job to ensure that only cannabis products were consumed in the grass area and to enforce the so-called Uncle Buddy safety rules in the pool area. Each morning I’d skim the cold pool, removing all bobby pins, nose clips, Band Aids and Baby Ruth bars. In the evening I’d pull the plug on the hot pool, releasing a steamy tsunami in the direction of Heber City. Overnight, the pool would slowly refill with fresh water drawn from the adjacent hot pot—which, prior to chlorination, was a beautiful emerald green. After chlorination, it tuned urine yellow and had to be tested periodically throughout the busy weekend in order to determine whether it was or was not, in fact, urine.

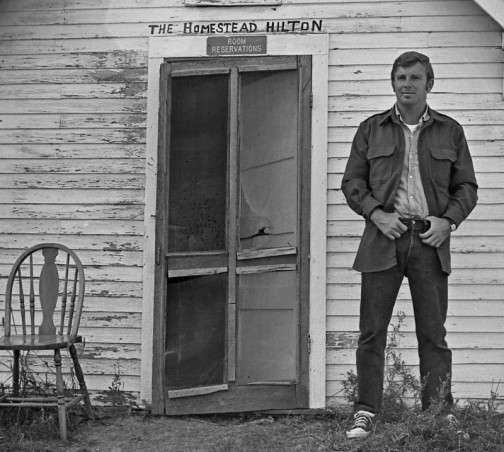

I felt sorry for those weekend visitors, who were paying good money in order to swim in spring water, breathe fresh mountain air and bask in sunshine that I enjoyed twenty-four-seven for free. “Quiet desperation,” was the phrase that sprang to mind as I gazed down from the lofty heights of the lifeguard tower. Sure, I was only earning a dollar and forty cents per hour, but so what? I had no living expenses save a $27 monthly payment on a 305cc Honda scrambler. Waitresses slipped me free food, and I lived rent-free in a one room shack I had dubbed “The Homestead Hilton.” It wasn’t much to look at from the outside; however, the interior was quite homey.

My shack sat beside Snake Creek at the far end of the compound, my relationship to the Whitakers being akin to that of Jett Rink to the Benedicts. My circle of friends consisted of frustrated teenagers, unhappily married women, hippie chicks, milk maids and washerwoman Mae Jones, who presided over “the help” from her own humble headquarters—Mae’s Shack. It was Mae Jones who mothered me whenever I needed mothering, and it was she who knew more about what went on at The Homestead than anyone. On a shelf in her shack was a collection of little bottle figurines—voodoo dolls, I suppose you could call them—each representing a member of the Homestead community. There was no greater honor than to become one of the little bottle people on display at Mae’s Shack, and I took great pride in being one of them.

Now and again the resort’s custodian Elmer Kohler would dispatch me to Salt Lake City to fetch a replacement part for something. Purchase order clinched between my teeth, I’d race my motorbike up Snake Creek Canyon, over Guardsman’s Pass, thence down State Route 190 through Little Cottonwood Canyon, dodging deer and skunks and porcupines along the way. At such times I could scarcely believe I was being paid to have such a good time!

Come fall, the resort would close—much to my dismay. Around the first of October, I’d pull last plug and—like the dutiful lifeguard that I was—go down with my pool. I’d then have to pack up and leave Brigadoon; however, I never found another place quite like Midway. So it happened I returned the following summer, and again the summer after that. Sadly, there came a time when I just had to start behaving like a grown-up. On my very last day I remember reaching my arms halfway around my beloved shack. I shed a tear then, as I’m shedding another tear right now—remembering the best job I ever had.