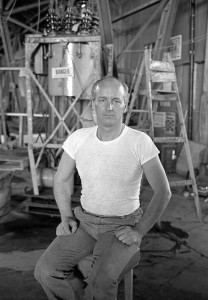

From a friend of his in Brockton comes the sad news that Robert K. Golka has died at the age of eighty. Because I’ve long been interested in people who step to a different drummer, it was inevitable that I would someday cross paths with Mr. Golka, and I count myself fortunate to have known him. What follows is a heretofore unpublished account of a trip I made three decades ago to Golka’s mountaintop laboratory high on a mountaintop outside of Leadville, Colorado:

“I’d appreciate it if you wouldn’t make me out to be a mad scientist.”

Not many folks around Leadville know Robert K. Golka or what it is he’s up to. He lives in a cheap rooming house with his dog Beach Bear, speaks in a crisp New England accent, dines alone and falls asleep to the dulcet ballads of Slim Whitman. And no, he’s not mad, but he IS different.

For the past 21 of his 50 years Bob Golka has pursued a singular quest: to tame the awesome power of lightning and turn it to good use. In his mountaintop laboratory he’s generated indoor electrical storms that rival Mother Nature’s own. So far he’s succeeded in creating static on AM bands for twenty miles around, but his eventual aim is to broadcast electrical waves that will carry to every corner of the globe.

“It’s like dropping a stone in a pond,” he explains. “The waves die out before they get to the shore. So you gotta make enough commotion that the waves come back; the wave has to go all the way around the world and meet you back at the antenna. Then you can reinforce it, get the “water” oscillating, and the waves get bigger and higher and higher.”

How big? How high? Golka speaks of something called the Schumann cavity that underlies the ionosphere sixty miles straight up. In the Schumann cavity, he reasons, an electrical impulse could be sent around the globe with less loss in amplitude than would happen in a transmission line, which typically loses power at a rate of about 35 percent per thousand miles.

In other words, space is a better conductor than copper wire. And according to Golka, it’s not just a theory.

“Take lightning storms, for example. Every now and then there’s a superbolt of lightning somewhere on earth, and it generates an impulse that goes around the world many times—seven to thirty times around the world. And that’s just one lightning strike.”

Golka figures by “thumping” the Schumann cavity with frequent electrical impulses—say eight times a second—he could eventually set up a rhythmic global wave many times more powerful than a lightning bolt. The energy could then be pulled out of the sky by receiving stations anywhere on earth. The result: a light bulb would glow in darkest Africa, thanks to power generated in Leadville, Colorado.

If all this sounds new, be assured it is not. Wireless transmission of electrical energy is an idea first proposed by the inventor Nikola Tesla almost a hundred years ago. At the time, Tesla was living in Colorado Springs, working in a one-man laboratory not unlike Mr. Golka’s. Similarities between the two men are many, in fact.

Nikola Tesla, like Robert Golka, was a loner and a maverick. Born in Smiljan, Croatia, in 1856, Tesla was both gifted and afflicted throughout his life by extraordinary visions. Years before the advent of radio and television, Tesla spoke of sending voices and pictures through the air. In all, Tesla is credited with over 120 inventions, most significantly the polyphase alternating current system that is the basis of virtually all commercial power grids today. Legend has it that Tesla drew the inspiration for his rotating magnetic field motor from observing the rotation of the earth around the sun.

In 1884 the young Tesla landed in America with just four cents in his pocket and immediately went to work for Thomas Edison. His association with Edison wasn’t a happy one, however, and almost from the start the two great thinkers fell to feuding. In particular, the two disagreed as to which is the more efficient power mode—direct current or alternating current. Edison was convinced DC was the wave of the future; Tesla was adamantly AC. The result of the dispute was that Tesla soon found himself out of a job, but then was subsequently rescued by industrialist George Westinghouse, who used Tesla’s plans to build the nation’s first large scale hydroelectric generating plant at Niagara Falls. Tesla’s patents made him a rich man (though not nearly as rich as Westinghouse) and provided him the wherewithal to pursue his lightning research.

By and by, Tesla attracted the attention and patronage of the great nineteenth century financier J.P. Morgan; however, their alliance was an uneasy one. Morgan was looking for marketable ideas, whereas Tesla cared only for pure research, marketable or not. When the mercurical inventor became obsessed with the notion of transmitting electricity without wires, Morgan’s wallet abruptly snapped shut. Morgan worried that without wires there would be no electrical meters, and without meters, there could be no power bills.

Robert Golka readily admits to a lifelong fascination with the work of Nikola Tesla. He’s made three trips to the Tesla Museum in Belgrade, where he managed to copy several pages of the inventor’s lab notes. Over the past two decades he’s attempted to replicate Tesla’s lightning experiments, with fair to middling results.

“I’m not sure he really had a good handle on this,” says Golka. “He had the concept, but the numbers he put down don’t work.”

One of Tesla’s experiments that hasn’t worked for Golka has to do with ball lightning, a seldom seen phenomenon that sometimes occurs during thunderstorms and is occasionally generated accidentally by high energy electrical equipment. At his Colorado Spring laboratory at the turn of the century, Nikola Tesla is reputed to have created ball lightning using a high frequency transformer, or Tesla coil. Tesla described it as “a wondrous phenomenon” worthy of further study.

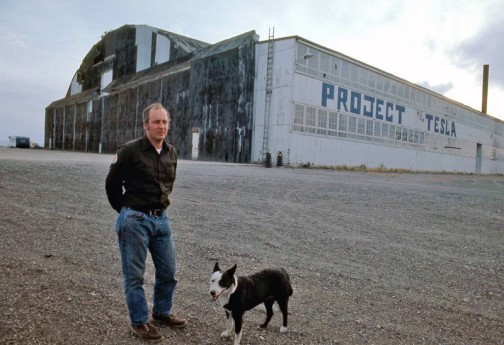

Determined to advance the study, Golka moved from his native Brockton, Massachusetts, to Wendover, Utah, where in 1974 he took up residence in a 60,000-square-foot aircraft hangar at Wendover Air Base. There he set about assembling the world’s largest Tesla coil from military surplus hardware and found parts. What he couldn’t buy, build or borrow, he salvaged from the town dump.

Golka’s theory is that ball lightning is a self-contained plasma sphere consisting of superheated ionized gases. If it were possible to replicate the natural force that holds the sphere together, he reasons, we might someday be able to use the same force to harness the power of nuclear fusion. The happy result would be a clean and inexhaustible source of energy for the future.

During his nine-year tenure at Wendover, Golka produced a lot of manmade lightning—crackling bolts of twenty million volts and more. But only once or twice did his monster coil yield up the elusive and transitory phenomenon of ball lightning.

Still, Project Tesla persisted, aided now and again by an occasional small research grant, but for the most part financed out of the solitary inventor’s shallow pockets. Times didn’t really get hard, though, until 1980, when the U.S. Air Force, which had been charging a nominal dollar per year rent on the hangar, donated the inactive air base to the town of Wendover. The town fathers immediately upped the rent 2,400 percent.

The rent increase precipitated a chain reaction that led to hard feelings, a civil lawsuit and the eventual acrimonious departure of Wendover’s one and only scientist. Mayor Hugh Neilson echoed the opinion of many of the townsfolk when he dismissed Golka as a freeloader and his experiment as nothing more than “a highly spectacular stage show.”

Following his eviction from Utah, Golka returned to Massachusetts, where he continued his lightning research using old railroad locomotive generators. Then in the summer of 1987 he went West again, relocating his laboratory to a large metal building he leases from the AMAX Mining Corporation. He brought with him thirty tons of equipment on three flatbed trailer trucks and a battered, but still buoyant sense of optimism.

Though ball lightning still interests him, Golka’s efforts today are more directed at proving Tesla’s theory regarding the wireless transmission of electricity, and like Tesla before him, he believes the rarified atmosphere of the high Rockies is a good place to start. From boards and timbers salvaged from the area, he’s built an 80-foot-tall resonating tower topped with a mast that telescopes 150 feet above ground level, which happens to be 11,400 feet above sea level. That’s still approximately 58 miles short of the ionosphere, but Golka figures it’s a step in the right direction.

“Now the question is whether we got enough power, whether the aura is big enough to get the (Schumann) cavity excited. The next thing I’m gonna do, I’m gonna probably get a big balloon and extend the tower up another 3,000 feet. An aerostat—it’s really more like a small blimp—and then you can raise a wire up and make the tower electrically taller.”

To this unscientific visitor, Golka’s mountaintop laboratory succeeds splendidly as a work of art. Like Willy Wonka’s Chocolate Factory, everywhere one looks there are wonders to behold. Mingled with dusty mining machinery and piles of giant earth mover tires is a wealth of electrical apparatus—transformers, generators, rectifiers, capacitors, switches, commutators, insulators—all of industrial strength and almost all of vintage manufacture. Most of it, like the sodium vapor street lamp that illuminates his workbench, has been repurposed from a previous life.

In the middle of the room sits the exploded innards of an x-ray machine. Tesla coils of various shapes and sizes and a Jacob’s ladder—standard props of science fiction films—snap, crackle, pop and sizzle overhead as Golka’s golden retriever Beach Bear dozes below, apparently oblivious to the fact wet dogs make excellent conductors.

It’s definitely a hardhat area. The daily afternoon hailstorm is amplified many times over as it beats down against the corrugated iron roof eighty feet overhead; lightning flashes outside followed by shuddering thunderclaps lend an atmosphere of drama and imminent doom. Doctor Frankenstein would be right at home here.

Robert Golka seems right at home as well, although there’s not the slightest evidence of creature comforts. His furniture consists of just three mismatched chairs and an end table, arranged before a burnt out television set and a nonfunctioning Westinghouse electric clothes dryer, which serves as a rat proof cupboard for groceries.

A frequent guest is 41-year-old bespectacled New York native Gary Peterson, who lives nearby in a trapper’s cabin. Peterson and Golka occupy two of the chairs. The third, according to the sign posted on it, is reserved for Nikola Tesla, who died in 1943. Thoughtful and introspective, Peterson is one of several so-called Teslaphiles living in the area. A member of the International Tesla Society headquartered in Colorado Springs, he subscribes to the society’s credo that Nikola Tesla was a man ahead of his time.

“Somewhere between 1900 and 1920,” he says, “there was a significant change in human thinking. The twentieth century went one way and Tesla went another.”

What happened was, science became more of a corporate effort while Tesla remained a visionary and resolutely independent thinker. Tesla claimed to have intercepted signals from outer space; he envisioned a hand held vibrator that could reduce the Empire State Building to rubble, a death ray that could bring down a thousand attacking aircraft in one shot. Toward the end of his life, he came to be widely regarded as a mystic, a charlatan, and a crackpot; however, a growing number of thinkers today are committed to revising Tesla’s reputation upward. They run the gamut from reputable scientists to pyramid power people. A scientific counterculture, so to speak.

Count Robert Golka among them, albeit with reservations. After spending half his adult life on the trail of the mysterious Mr. Tesla, he’s beginning to wonder where it’s leading. As he walks back to his humble rooming house in the rain, his mind turns to practical matters: the rising cost of rental space, the rising cost of gasoline, the rising cost of copper wire and guillotine switches from Radio Shack. Like Tesla in his later years, the Brockton bachelor is running short on funds. Come winter he’ll have to close his lab and look for electrical consulting work, perhaps mundane employment repairing jukeboxes and pinball machines. Over the years he’s accumulated a hundred marketable skills, so he could find work anywhere. But he’s not much interested in looking.

“Making money bores me to death, it really does,” he declares. “I’d do this work for nothing, the rest of my life. It’s fascinating—it’s better than being a millionaire and having Rolls Royces and big homes around the country.

“The thing is, you have to make your own decisions without having to go to a board meeting to convince a committee. I mean, that’s what the whole problem is. The trick is, you have to maintain your own individuality. And you know, we’re losing that just terribly in this country. We go to universities, we get conditioned to the point that, you know, we gotta be just like everybody else. And I say phooey on that.”