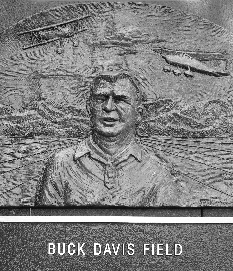

You know you’re getting on in years when you start coming upon bronze plaques of people you used to know and historic markers affixed to places where you used to work. Sadly, Carbon County officialdom has yet to acknowledge my many contributions to aviation history in Southeastern Utah. For example, I was the kid who successfully talked Wayne Baker down the night he got lost in the clouds. This in spite of the fact I had no training in air traffic control whatsoever. Mainly what I did at the county airport was listen for a familiar static pattern on the Unicom, which meant the boss’s 1956 Oldsmobile was on approach. Time to bestir myself and get busy sweeping the hangar, dusting off airplanes, darning the windsock. Presently, the boss would settle into his office chair and there he would sit for hours upon hours on end. In the history of fixed base operators, none was ever more fixed than Buck Davis.

Now and again Buck and his wife Frances would pack themselves into the Cessna one-eighty and fly off to Nebraska, or wherever it was in the Midwest that Buck had played football on a team noted for its beefy front line. The Six Blocks of Granite, I believe they were called.

Once the cats were away, the mouse would play. If there happened to be a nice aircraft parked on the tarmac, I’d pretend it was mine. I’d wave a cheery goodbye to my imaginary friends, of whom I had many. Fact is, I pretty much had the county airport all to myself—which was fine by me. I was a teenage hermit.

Should an airplane land, my job was to gas it up and tie it down. In addition to our own fleet, we were home to two or three private aircraft, as well as a Piper Super Cub that belonged to the Fish and Wildlife Service. Equipped with a belly tank, the Cub was used to plant rainbow trout in high mountain lakes along the Uinta Range. Said trout didn’t wear parachutes, which meant the pilot had to fly low and slow over the target. Drop your load too soon or two late and the airborne fingerlings would land not in the lake but high on a rocky ridge, resulting in fossilized impressions sure to baffle future paleontologists. This was dangerous business, and in order to steady his nerves the pilot kept a fifth of Jim Beam behind his seat.

Ours was a high altitude airport, surrounded by even higher mountains. Whenever storm clouds were brewing, departures were discouraged, but of course I didn’t have the authority to issue cancellations. So what would happen is, I’d find myself entertaining some frustrated pilot who was just dying to resume his cross-country trip. “What is there to DO around here?” he’d ask, and I’d just shrug. Why would a young buck like me be hanging out at the county airport if there were anything doing in town?

As the hours dragged on and the overcast refused to lift, a strange thing would happen. The grounded pilot would see an imaginary opening, and off he would go into the wild gray yonder, never to be seen again.

The day what remained of the Fish & Game’s Super Cub came back on a flatbed trailer was the day I began to rethink my desire to fly. The mortality rate among private pilots is alarmingly high, second only to the suicide rate among junior high school band directors. Which is why, after giving the matter considerable thought, I let my student pilot license expire and also quit taking trombone lessons.