On blustery winter days like this I spend a lot of time reminiscing about how I got started on my so-called career as a journalist. By all accounts it is an occupation for which I am uniquely unqualified—as duly noted by the general director of KUED, the University of Utah’s television news station—who pointed out that my application included zero academic credentials. Not only had I never taken a journalism course, I’d been refused admission to the university!

Unable to find gainful employment, I’d retreated to a one-room shack in the woods, where I lived frugally and read a lot of Henry David Thoreau. By and by I became acquainted with a young woman whose family owned a television station in Salt Lake City. Our paths crossed because she had “dropped out” whereas I had been “kicked out.” Diane greased the skids and next thing I knew, I was a stringer for intermountain NBC-affiliate KUTV. My assignment was to drive to some distant community inside the signal area and film something—anything—in order to satisfy an FCC requirement of some sort.

What made it interesting was that KUTV would place an ad in the local community newspaper announcing an upcoming feature when in fact no such feature had yet been filmed. Sometime between the announcement and the air date it was up to me to go out and shoot something. Needless to say, this put quite a lot of pressure on me to produce.

I never called ahead; I just drove out in hopes of finding something. I’d drive up and down Main Street in search of “news.” Sometimes I’d pop into the local newspaper office, hoping for a tip, but I never got anything useful. Local newspaper editors are focused on issues of local import, such as curb-and-gutter projects. If I were to ask, “What about that fellow wearing animal skins and riding on a dog sled that I passed on the road?”—the answer would be, “Oh, HIM!.”

Of course, I would go after the oddball on the dog sled. Why? Because, having been an outcast, I have no trouble talking to them, nor they to me.

Most of the time, unfortunately, there was no misfit on a dogsled to be seen. As the day wore on, I’d become increasingly desperate. Come nightfall, I’d check into the cheapest place in town, which in Ely, Nevada, was the Hayes Hotel, where a room went for two dollars per night. I remember lying in bed, perusing the Gideon Bible until my eyes began to sting. I checked the bulb in the reading lamp. It was about ten watts, still cool to the touch.

In the morning I continued my quest. I ended up at the county hospital, interviewing a respected doctor named William Bee Ririe, after whose retirement the hospital would eventually be named. I asked Doctor Ririe if he would mind if I followed him around for awhile as he examined patients, maybe filming an operation or two. He wasn’t keen on the idea.

“It’s very bad form for a physician to indulge in self-promotion,” he said. And with that, I was out on the street again.

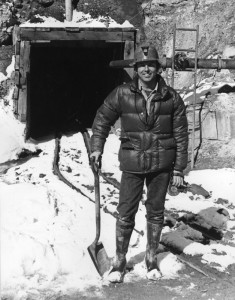

Subsequent experience has taught me that a town like Ely, Nevada, is actually brimming with human interest stories—provided you know where to look. However, at that time I didn’t know where to look, or how. As the afternoon wore on, I found myself sitting atop a hill at the edge of town, slowly sinking into despair. That’s when an old miner named Fred Ferguson appeared, come to inspect a claim he’d worked many years earlier. I asked if I could tag along, and he said, “Why not?”

Fred showed me some things I hadn’t noticed before. A hole in the ground here, a head frame there, and something called a star churn drill. I filmed him as he demonstrated how it worked. “Would you like to be on television?” I asked.

“Why not?” he answered.

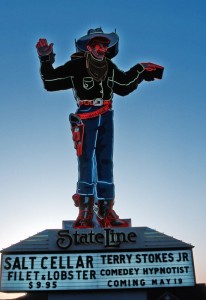

I left Ely that night with two hundred feet of 16-mm Ektachrome in the can and a notebook full of notes. At Wendover, I stopped at the StateLine Casino and gambled away my last twenty cents on the slots. On the second dime, I hit a ten-dollar jackpot. I bought myself a steak dinner with all the trimmings. It was one of my better outings.