An estimated 42 percent of professionally trained teachers quit within five years of starting the career of their choice. Here in Utah, it has been proposed that they could be replaced by teachers who are not professionally trained. There was a time in my life when I thought this might be a good idea. I no longer think so.

Here’s why. I stepped into an actual classroom. An hour later I slunk out, tail between my legs, ego hopelessly deflated and giving thanks to God that I didn’t have to teach six more units that day. Whatever they are paying teachers nowadays, it’s clearly not enough.

Of course there are some in the teaching profession who should probably be paid less, and you know who I’m talking about because you, too, have had the same teachers. Usually, it’s someone who is teaching a course about which he or she knows nothing. For example, I learned nothing about history from Jackson Jewkes, whose strong suit was coaching football. If you were involved in the football program at Carbon High School, the very last word you’d ever want to hear is “history”

At that same school, my father taught Industrial Arts, This was back in the Nineteen Fifties, when juvenile delinquency was rampant and shop classes were akin to reform school. What to do with that kid who’s been caught with a switchblade knife in the pocket of his black leather jacket? Why, transfer him to woodworking, and hand him a power tool!

Once, my father came home from work with a black eye. It broke my heart. Then and there I swore that I would never become a teacher, even though my parents assumed I was headed in that direction. Why? Well, because my strong academic suit was English, and what else can one do with a college degree in English but teach?

Well, here’s one thing: You can sweep floors and pick soggy cigarette butts out of urinals for one dollar and forty cents an hour. That’s what I was doing in the summer of 1967, and to tell you the truth I didn’t mind it. Janitorial work requires little in the way of concentration, so even as I picked up those soggy butts, my higher cognitive functions were unburdened. I could daydream and cogitate to my heart’s delight, and herein lies the true value of a liberal education. If you can read, if you can write, if you can think, then menial labor isn’t all that oppressive. So long as the people who look down on you are stupider than you are, their insults will just roll off your back, same as urine bounces off a petrified wad of discarded chewing gum lying in the bottom of a urinal.

Come fall, the summer resort where I was working would be closing, however—which meant I’d have to find another job. Perusing the want ads, I came upon a listing for a school teaching position in Jordan Valley, Oregon. NO EXPERIENCE NEEDED, it read. NO TEACHING CERTIFICATE REQUIRED.

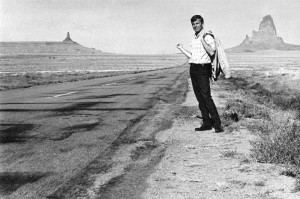

I answered the ad and was promptly invited to a job interview. I managed to scrape together twenty bucks to buy an airplane ticket to Boise, and from there hitchhiked the rest of the way to Jordan Valley. My first ride was on the back seat of a motorbike; the second in the bed of a flatbed truck. By and by, I staggered into the tiny ranching community of Jordan Valley, looking a bit disheveled and smelling of rotten potatoes.

“Are you the new schoolteacher? I heard a woman’s voice from the doorway of a farmhouse. Turned out she was head of the local school board. Presently, I found myself facing the entire board: stout farm wives and ruddy-faced, raw-boned cowboys.

“So,” I began. “What sort of books do your children like to read?”

“Horses,” they answered in unison. “Anything about horses. And cows.”

And here I was thinking we might be exploring the ontological density of Moby Dick.

Following the interview, my right hand crushed repeatedly. Evidently I’d aced the interview even though I know squat about horses. The school board lady showed me around town, which consisted of one saloon and a small boarding house in which my predecessor had lived. Was that a bloodstain on the carpet? Yellow ribbon on the old oak tree out front–or police tape?

My trip back to Salt Lake City was arduous. Mostly I hitchhiked, but had bailed from a hopped up Mustang on the outskirts of Bliss, Idaho, fearing that the two young men who had picked me up were plotting to kill me. I had just enough money left in my pocket to buy a Greyhound bus ticket to Tremonton, at which point I’d already decided I didn’t want the teaching job in Jordan Valley.

“Thank you so much for the job offer,” I told the school board lady over the phone. “But evidently my draft board has determined I’m needed in Vietnam.”

“Oh, we can fix that,” she answered. “Let me talk to your draft board.”

“Oh, no, please don’t,” I said. “I’ve thought it over, and all I want to do right now is die for my country.”

That was a lie, of course. Not only did I not want to die, but I had already been found unfit for military service due to a mental problem of some sort. Technically, it was temporary insanity; however, to this day no one has ever bothered to upgrade my condition.

So that was my first brush with the teaching profession. The last came many years later, when my son Alex was a first grader at a teacher-parent co-op school. Once a week, I was obligated to teach a small group in whatever subject I found interesting. I chose to talk about photography—something that has fascinated me from the time I was a little boy. I brought along a box of photographic paper, a printing box, some darkroom chemicals.

“Watch closely now, and see how the light-sensitive emulsion reacts to a brush dipped in Dektol. Is this magic, or what?

“It’s kinda boring, Dad,” said my son. “Would it be okay if I went to another group?”

That’s when I knew for sure that I don’t have what it takes to be a teacher. Or even a guest lecturer! Oh, sure, I still give it a go now and again. But whatever they’re paying me, it’s way too much.