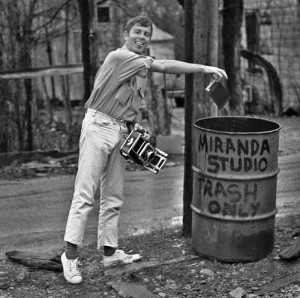

What follows is a true story, not something I just made up in order to make a buck. It all began in January, 1969, when I was living in San Marcos, Texas—if “living” is the right word for it. Actually, I was camping in a wood-paneled garret above a portrait studio, where I worked as a photographer’s assistant. Below, in equally humble quarters, lived my fellow assistant, the enigmatic Senior Acosta, whose signature phrase was, “Smile now, pay later.”

I’d taken the job to satisfy my mother, who insisted it was high time I got started on a career of some sort. Because I’d always been keen on photography, she assumed that I’d be happy to spend my life shooting weddings, group shots, passport pictures and beauty queens. What she didn’t know is that I was much more interested in documenting the lives of those who live outside the mainstream of society. In other words, people like me.

Nighttimes, I would sit at my table pecking away at my Underwood electric typewriter. My goal was to crank out something that would sell and thus establish myself among the pantheon of published writers. I was having no success whatever, but then came a letter from home. Evidently my young niece Annette had said something about hippies that her grandmother found amusing. “Would you please type it up,” Mom wrote, “and send it on to The Reader’s Digest.”

I did as I was told, even though I didn’t find my niece’s observation regarding hippie hairstyles the least bit amusing. In fact, I prefaced my submission to the editors with words to the effect that I was only sending it in at my mother’s urging. Then came a thought: as long as I was springing for a postage stamp, I might as well attach a submission of my own.

First, I needed a setting. I settled upon “a small mountain resort in the Utah Rockies” where I had worked as a lifeguard the previous summer. It was a dark and starry night. I was sitting on the deck conversing with a visitor to the resort, a man from a big city. But which big city? I decided it would be New York City.

The two of us were “comparing the relative merits of country and city living. I argued that country people were more realistic and down-to-earth; he claimed that out here we were too sheltered from the hard realities of life.

“Later, as we walked to our cabins, we paused to gaze at the stars. It was a moonless night, so clear that every star and constellation was visible. ‘Goodness,’ exulted my friend, ‘it’s just like a planetarium!’”

Two months passed, and then it came. My first acceptance letter, along with a check in the amount of two hundred dollars! Two hundred bucks, as much as I was pulling down as a photographer’s assistant each month, and for just two paragraphs. My wildest dream had come true! I immediately quit my job and hopped a bus for Austin, where I moved in with a girl I had met in the Peace Corps. Whenever people asked what I did for a living, I’d tell them I was a writer. And I still do, even though I’ve yet to sell another word to Reader’s Digest.

Fast forward exactly ten years. I was now roaming the Western United States in a Volkswagen Kombi, snapping pictures, taking notes, recording interviews, and submitting articles to various magazines. It didn’t pay much, and my mother didn’t approve, yet it was pretty much exactly what I wanted to do with my life.

One day I found myself sitting in a restaurant in Eureka, Nevada. Seated across the table was Jack Killinger, Eureka’s foremost eccentric. “So, what brings you way out here?” he asked.

“I love the open spaces,” I said. “I love the freedom to camp just about anywhere I want. Oh, and the stars at night! So much brighter than in the city.”

“Funny you should say that,” said Jack. “There’s a story I’ve heard about these two tourists who were driving along Highway 50. They were from New York City. It was nighttime, and the two pulled over and got out of the car to stretch. This guy from New York, he looks up at the heavens in amazement. ‘Goodness,’ he exclaims, ‘it’s just like a planetarium!’”