Sifting through my library today, I’m surprised to find not just one but two copies of a book about Jarbidge, Nevada—both autographed by the author, Helen E. Wilson. I’m reminded that thirty-five years ago I set out to write a magazine story about Jarbidge, only to end up shelving my notes after concluding that at least half its two dozen citizens must be on the federal witness protection program.

My photographer colleague Adam Jahiel has a similar observation regarding his adopted home of Story, Wyoming. “I don’t know how many people live in Story,” he told me. “I have no idea how big it is, even. From the air, you can’t even see it.”

I was interested in Jarbidge because it’s extremely remote and hard to get to. Because it lies at the bottom of a steep canyon, I surmised the television reception must be lousy. Towns without TV reception are always more interesting, since the people who live there have no choice but to interact with one another and even speak to strangers in town such as myself. The first resident I interviewed was O.K.Grant, a former trappist monk who had left the monastery because of—in his words—“all the stress and strain.” Not to mention, the noise.

I can only imagine how bad that might be. “Will you brothers please put a sock in it? That’s the third word I’ve heard out of you just this week!”

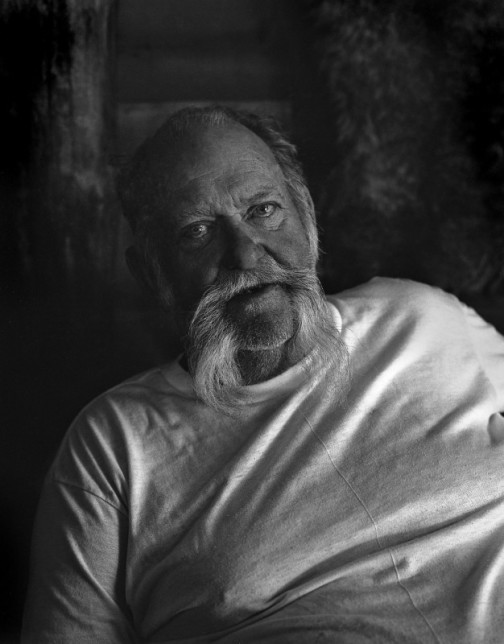

Brother Grant’s passion was making wine and sharing the same with passersby. Presently, I was buzzed and unfocused as I staggered along Jarbidge’s single street. In front of a chalet-style cabin was a woodpile with a sign warning would-be firewood thieves of hidden explosives. Next to that was another sign offering a fifty-dollar reward for information leading to confirmation that the proprietor of the booby-trapped woodpile, a man named “Smitty,” had been drinking. Soon afterward, I found myself searching Smitty’s rheumy eyes for signs of insobriety. I took a picture, in case I’d be needing evidence in order to collect the reward.

Turns out Smitty was relatively sober and coherent. He told me he’d previously been a resident of Las Vegas, where he had the foresight to buy property alongside south Las Vegas Boulevard back when it was still just open desert. As a result, he had no money worries—nor did his friend and neighbor Roscoe Fawcett, heir to the Fawcett Publishing Empire and the person who had posted the reward.

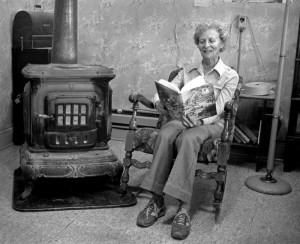

I next wandered into a bar, then quickly wandered back out, realizing I was still buzzed from the fugitive monk’s homebrew. I vaguely remember chatting with Helen and Grace Wilson, sisters whose father, Jack Goodwin, had been a prospector back when Jarbidge was a booming mining camp. Helen and Grace had nothing but fond memories of their frontier girlhoods, and though both had traveled widely in their adult lives, Jarbidge remained their home base and psychological touchstone. What a great time it must have been, to have come of age in such an unusual, off-the-grid place! And how smart of Helen to write a memoir, knowing that just about every reporter and tourist who comes to town will buy a copy—because, after all, what else is there to buy in Jarbidge?

Shortly thereafter I received a nice letter from Helen thanking me for my purchase. She wondered how my little daughter was doing—which is odd, because I don’t remember ever having a little daughter. Then again, I WAS drunk.