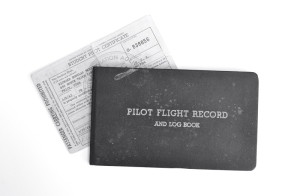

As my mother’s mind began to unravel in the Nineteen Eighties, she set about getting rid of everything in her house that once held sentimental value. Documents, mementos, diaries, photograph albums, books—the sort of stuff normal people will rush into a burning house to save—all of it went into the trash. What didn’t get tossed was my late father’s workbench, which was too heavy to drag to the curb. That workbench now sits in my garage, and the other day, tucked away in a hidden compartment in the back of the top drawer, I found a treasure: A pilot’s logbook documenting my history as an aviator!

According to my student pilot license, dated 3/20/62, I once weighed 140 pounds and had hazel-colored eyes. Stapled to the certificate is a medical certificate signed by Orson Spencer, M.D., certifying that I have “met the physical standards prescribed in Part 29, Civil Air Regulations.” In the blank reserved for “limitations,” Doctor Spencer had optimistically typed “None.” Evidently, no one fact-checked that certificate. My eyes are and always have been green. And had the doctor ever flown in an airplane with me at the controls, he surely would have revised his opinion regarding my lack of limitations.

Fact is, I’m not a great pilot, but I do love airplanes. I love being around them, and I loved hanging out at the Carbon County Airport, where I once “worked” but mostly just hung out. My boss was E.L. “Buck” Davis, also known as an FOB. Fixed base operators are pilots who seldom get to fly because they are charged with minding the airport. Whenever Buck would take a drive into town, I’d become the FOB, an when he returned, he always found me hard at work: sweeping the hangar, dusting the airplanes, darning the windsock. He often said I was the hardest working assistant he’d ever had. What Buck didn’t know is that the spark coil on his 1956 Oldsmobile created a signature static pattern on the Unicom transceiver. So I always knew when he was coming, five minutes in advance.

Teenaged FOBs don’t normally thrive, but I did. I reveled in the solitude, the quietude, the spacious skies and scenic vistas. To the west rose the Wasatch Plateau, to the north and east the Book Cliffs. To the south lay the San Rafael Swell and Canyonlands. The high desert air smelled of sage and juniper; the hangar smelled of carburetor cleaner and WD-40. On one wall was a calendar featuring Elvgren pin-ups; on another was a sign advising that the airport was not responsible for damages by fire or theft by Carbon County commissioners. Part of my job entailed keeping an eye out for those thieving commissioners.

The job paid one dollar per hour, half of which went toward flying lessons. In other words, thirty hours on the ground translated into half an hour in the air—behind the controls of a Piper J3 manufactured in 1943, the same year I was born. The cub had a tandem cockpit; Buck sat in the front seat, I in the rear, so pretty much all I could see was the back of my instructor’s head. According to my logbook, our first flight was “straight and level” with “medium turns.” By lesson four, we were doing steep turns; by lesson ten, “approaches, landings, and takeoffs.”

Landings and takeoffs. To become a genuine aviator, you’ve got to master landings and takeoffs, and—hardest of all—you’ve got to deal with cross winds. I dreaded crosswind landings! For one thing, I could never see out the front window. The cub had a tail wheel, which means you had to set it down with its nose in the air. From the back seat, if I could see the runway ahead, it wasn’t a good sign. It meant that I was coming in sideways.

Together, we two had logged eighteen hours of airtime before finally my instructor decided it was time for me to solo—this on the bright and clear morning of May 19, 1962. We’d been doing touch-and-goes for about forty minutes, when Buck braked the airplane to a stop and climbed out.

“It’ll get off the ground a bit quicker without me in it,” he advised.

Holy shit, did it ever! No sooner had I pushed the throttle lever forward than the little cub with its screaming 65-horse Continental engine was airborne. How strange it was to be the sole occupant of an airplane! For the first time, I could see out the front window, past the unoccupied forward seat where my instructor’s joy stick and rudder pedals moved as if by an invisible hand and feet. For the first time, I noticed that the J3 had an instrument panel—this in addition to a rudimentary fuel gauge, which was nothing more than a cork inside the gas tank, attached to a wire that protruded from a hole in the top of the cowling.

Mechanically, a Piper J3 is nothing more than an upscale model airplane. All it lacks is a string attached to the wing, which in effect it had—an invisible string that was held firmly in the grasp of my ground bound instructor. I could almost feel Buck tugging at me as I banked left, returned to the airport and banked left again, then still again. I de-iced the carburetor, backed off the throttle, and straightened her out. Runway, here I come!

They say that any landing you walk away from is a good landing, but Buck didn’t call mine good. He just wrote “satisfactory” in my logbook.

My parents never came out to the airport to watch me fly. I suspect they might have been against the idea, although they never said as much. Pretty much every dream or scheme I ever came up with when I was young was met with stony parental silence; however, I like to think that because my father hid my pilot’s logbook in a place where my mother couldn’t find it and throw it away means that, in his own quiet way, he was secretly proud of me.