Nowadays it’s fashionable to poke fun at the Nineteen Seventies, in particular the period’s bizarre sartorial and tonsorial fashions, but I remember it as an interesting decade when ideas were in the air. Sophomoric and half-baked ideas for the most part, but ideas nonetheless.

One of the big ideas of the Seventies was that people could pool their resources and live communally. This meant sharing living quarters, sharing food, sharing chores and sharing sexual partners. Alas, it turns out that human beings don’t necessarily like to share sexual partners. Or be shared, as it were.

I never belonged to a commune, but because I was roaming the West in a VW Kombi, I was looked upon as a likely recruit. “Welcome home, brother,” is how I was greeted at a Rainbow Family Gathering. “Do you have any spare change?”

The nomadic Rainbow Family has no fixed headquarters and no spiritual leader—not since Jerry Garcia died, that is. So it’s a wonder it has survived all these years. Usually, whenever a charismatic leader dies, his or her commune dies out soon afterwards. That is, unless the commune has become rich and politically powerful, in which case a board of directors will be appointed to carry on the good work of the late, great guru.

One whose innovative social experiment has since petered out was the libertarian polygamist Alex Joseph of Big Water, Utah, who in the mid-Seventies had accumulated seventeen attractive young wives. Unlike the sister wives of nearby Colorado City, his were college educated and self-reliant. One of them told me that she considered polygyny liberating in that she didn’t have to do all the housework and baby sitting, and was thus free to pursue her career as a lawyer. Alex himself had no time for housework or baby sitting as he was too busy making public appearances, courting new women and fighting the feds over this and that.

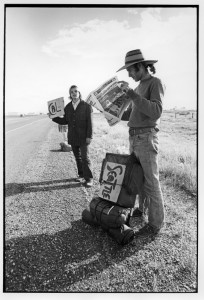

Joseph styled his hair in braids like an Indian and sometimes wore a Geronimo hat, same as Billy Jack. Posing as a Native American was a great way to attract acolytes. Take, for example, erstwhile railroad man John Pope of East Carlin, Nevada, who adopted native dress and renamed himself Rolling Thunder. Thunder soon became a counterculture celebrity—thanks largely to a biography penned by Douglas Boyd. If you were a young person on a vision quest at the time, your backpack would most likely contain a copy of Boyd’s book ROLLING THUNDER, and also Carlos Casteneda’s THE TEACHINGS OF DON JUAN: A YAQUI WAY OF KNOWLEDGE.

I passed by many times, but never visited Rolling Thunder’s commune. Once, I phoned and attempted to set up an interview, only to be met by maniacal laughter. Following Thunder’s death in 1997, the peyote smoke clouds dissipated and the so-called Thunder People disbanded. Today the teepees and foam domes are no more and the compound once known as Meta Tantay has become a storage yard for heavy mining equipment.

According to Wikipedia, Rolling Thunder had bit parts in THREE Billy Jack films. However, I know of at least one commune that that owes no debt to Tom Laughlin. The School Of The Natural Order, or Home Farm, situated a few miles up the road from Baker, Nevada, on the east flank of Mount Wheeler was founded in 1957 by Ralph Moriarty deBit, aka Vitvan. I stumbled upon the commune late one evening after taking a dusty back road, which terminated at an incongruous Dutch colonial style farm house encircled by tents and trailers. In one trailer I was greeted by longtime resident Barney Taylor, who divided his time between Baker and San Francisco, where he worked as a merchant seaman. We were soon joined by a pair of young hippies and a stunning redhead, who I recognized as a former dealer at Jim’s Casino in Wendover. The five of us had a grand time that night drinking and discussing the works of Alfred Korzybski and Georges Ivanovitch Gurdjieff—and of course, Vitvan—or “Vittie” as he was affectionately referred to by his inebriated followers. I learned that Vittie had passed away ten years earlier, but not before leaving behind a hundred hours of tape-recorded lectures explaining the origin and nature of the Ancient Gnosis.

Some years afterward I spent a night at the commune’s dormitory—because motel rooms in Baker were filled and it was January and too cold to sleep in my Volkswagen.

“During the night you will be joined by two women,” said the caretaker.

Turns out the dormitory has just two beds. Doing the math, I determined that one of the three of us was going to end up sharing a mattress. So I lay there and wondered, and wondered some more since there was nothing to read, no television to watch and no radio except for a dusty old war surplus transceiver. Evidently, for much of its history the Home Farm had been totally disconnected from the outside world except for short wave radio. I suspect that’s the way Vitvan liked it.

As for the two promised women, they never materialized. Turns out Gnosticism is different from other counterculture pursuits, in that the path to enlightenment isn’t lined with girls.