In Nevada, nothing is permanent. Mining camps rise and fall, casinos are imploded, and marriages last only for so long as it takes to drive from Las Vegas to Reno, save perhaps one brief interlude of connubial bliss in, say, the Mizpah Hotel in Tonopah. Once in Reno, the marital contract is quickly negated at the courthouse, after which the jubilant divorcee can walk the short distance to the Virginia Street Bridge and toss her wedding band into the Truckee River.

That’s what the character played by Marilyn Monroe in “The Misfits” did. Rumor has it that real life has often imitated art, although there is no way of knowing exactly how many wedding rings lie at the bottom of the river. That is, until a part time prospector by the name of Charles Carpenter set out to sift the sediment in search of castoff sentiment.

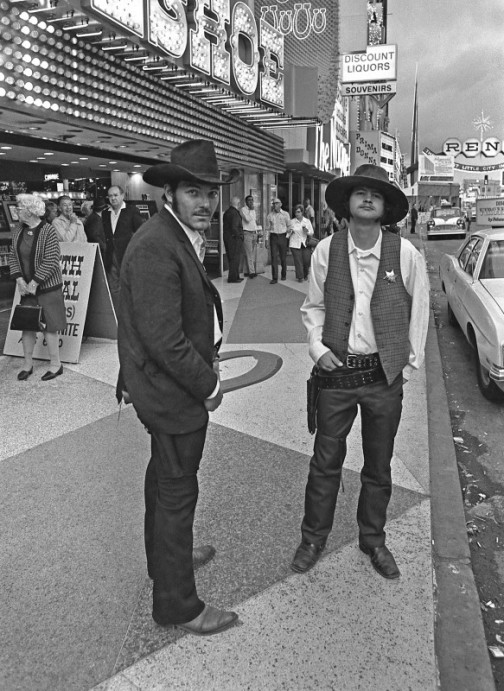

The year was 1973 and I was a young reporter determined to go wherever I sensed lay a good story. And thus it happened I found myself wading knee-deep in the Truckee, slip sliding over mossy rocks while balancing a Leica M3 in one hand and a Bell & Howell DR 70 movie camera in the other. No other reporters were in sight as I picked my way toward the spot where Carpenter and his sons operated a small gasoline-powered sluice. Overhead, a gallery of onlookers leaned over the wrought iron railing. The mood was festive, and for one brief, shining moment I felt myself not being depressed in Reno.

See, I’ve never cared for the so-called biggest little city in the world—not since the eighth grade when I failed to identify “the home of the free and the grave of the home.” In fact, nobody in my class got the answer. What the hell was a question like that doing on a quiz for eighth graders?

I’m pretty sure I’m the only one of my classmates who even remembers the question, let alone the answer. That’s because some things just get stick in my head and won’t go away. In particular, I remember every sad thing that ever happened to me—not just quiz questions I couldn’t answer but also every pet that died, my seventh birthday party when nobody came, every girlfriend who got away, every rejection letter, every boyhood dream that failed to materialize. And let me tell you, Reno, Nevada is NOT the place to be if you’re of a morose disposition. Take a stroll along Commercial Row and you will see the pitiful human condition laid bare. Perhaps it’s different if you have money in your pocket; I wouldn’t know. I’ve always been broke in Reno. In fact, following my encounter with Mr. Carpenter and his sons underneath the Virginia Street bridge I had to bum gas money from a station attendant in Lovelock in order to make it home.

And now, guess what? The bridge is being torn down in order to make room for a newer one. Local historic preservationists—all three of them—are distraught that a ll5-year-old landmark couldn’t be saved. Well, what did they expect? Nothing lasts in Nevada—not casinos, not mining camps, not marriages, not even the beloved shoe tree. Legend has it, the first pair of cast off shoes appeared shortly after a lover’s quarrel. Whoever cut the tree down in the middle of the night was perhaps trying to salvage something from the past. Or—which is far more likely—was determined to erase it.