Still another artifact from my early life is going away. A coal-fired power plant that has been a fixture in Carbon County for the past six decades ceased operating this week and will be dismantled for scrap over the coming summer. The plant’s current owner, PacifiCorp, claims the old plant isn’t worth upgrading in order to meet current environmental standards. The Sierra Club rejoices; local residents lament that the plant is a casualty of the so-called “War on Coal.” Given that over two thousand Carbon County miners have been killed in cave-ins and the like, including 171 men and boys who perished in the Castle Gate mine disaster of 1924, I think it’s safe to say that if, indeed, there is such a thing as a war on coal, the coal appears to be winning.

As kids, we LOVED the power plant and its adjacent coal mine, no matter that half of us were orphans and we all suffered from respiratory distress. Shortly after the plant first came on line in 1954, our sixth grade class was treated to a guided tour. I remember how impressed we were by the boilers, the turbines, the steam. In particular, we boys were keen on the steel mesh staircases and catwalks, which afforded tantalizing glimpses into the recesses of crinoline-buoyed skirts that swished overhead.

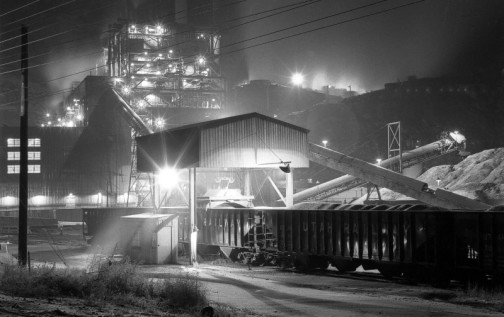

Years later, I would visit the plant late at night with my camera. I was fascinated by all the lights, which on film radiated star-like spokes–the number of spokes corresponding to the number of blades in the lens’s iris diaphragm.

Today’s Salt Lake Tribune places the plant “north of Helper” in “central Utah”—which just goes to show how ignorant big city newspaper journalists are. In fact, the plant is situated squarely in the eastern Utah community of Castle Gate. Alas, all that remains of Castle Gate today—other than the power plant–are a few foundations and a graveyard . Even the geographical feature that gave the town its name has been partially removed—in order to widen a section of U.S. 6 through Price Canyon, famous as one of the nation’s most dangerous highways. In the old days, the narrow highway wound between two towering monoliths, or “gates,” which would appear to open as you approached, and then close behind you once you were through.

There was also a tunnel—a very scary two-way tunnel just wide enough to accommodate one coal truck and maybe half a school bus. Two passenger cars could pass without touching, but it was close, so you had to pay attention and stop wondering whether the castle gates were opening or closing. The last thing you saw before disappearing into the tunnel was the great gray Utah Fuel Company tipple; the first thing you saw as you came out was the power plant, shrouded in smoke and steam and surrounded on all sides by mounds of coal and fly ash. If you were taking an upstate girl home to meet your parents, the romance was pretty much over by the time you emerged from the Castle Gate tunnel. At the time, I thought that was a bad thing; however, now that I’ve grown older and wiser, I realize it’s better to find out early on whether you girlfriend has the right stuff, which is something not evident in your typical tunnel of love.