“One crowded hour of glorious life

is worth an age without a name.”

— Thomas Osbert Mordaunt

“A little bit of something is better

than a lot of nothing.”

— Ron Booth

As funerals go in Provo, that of the late Ronald Booth was fairly typical. The pews were occupied by the sort of upstanding Utah County citizens one can always count upon in times of sorrow. The ever-reliable Relief Society sisters had prepared a feast that included the obligatory tuna-noodle casserole, plus a glutinous greenish concoction of canned fruit cocktail tidbits congealed in lime-flavored Jell-O, topped with tangy dollops of Miracle Whip and sprinkled with shredded cocoanut. The ward organist struggled valiantly to maintain a dignified tempo, ignoring as best she could sporadic screaming fits of restive toddlers.

Jack Booth, a Mormon bishop and cousin of the deceased, opened the service. Brother Booth began by apologizing for the delay in getting the church doors unlocked, and also for unspecified “problems” that had transpired at the mortuary. As a result of those problems, he added, “Ron is not with us today.”

Everyone in the chapel looked around. So that’s what’s missing—the body!

The irony of the situation wasn’t lost on another of Ron’s relatives, Bob Booth, who recalled that his late cousin had always been something of a slowpoke. “I always warned him,` Ron,’ I said, ‘if you don’t hurry up, you’re going to be late for your own funeral.’ And now, look what’s happened.”

Other speakers followed, including a nephew named Craig, who remembered his uncle as being “a fitness advocate long before it was popular.” Craig also remembered the day Ron came home from paratrooper school at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, a spit-shined, clean-shaven, gung-ho intelligence specialist assigned to the 101st Airborne. Uncle Ronnie celebrated the occasion by buying himself a brand new 1964 Chevy Impala 409, the most powerful production car of the day. Then he and Craig set out on a deer hunting expedition up Diamond Fork Canyon, pausing in Springville for a ceremonial sip of water from Ron’s “lucky” drinking fountain.

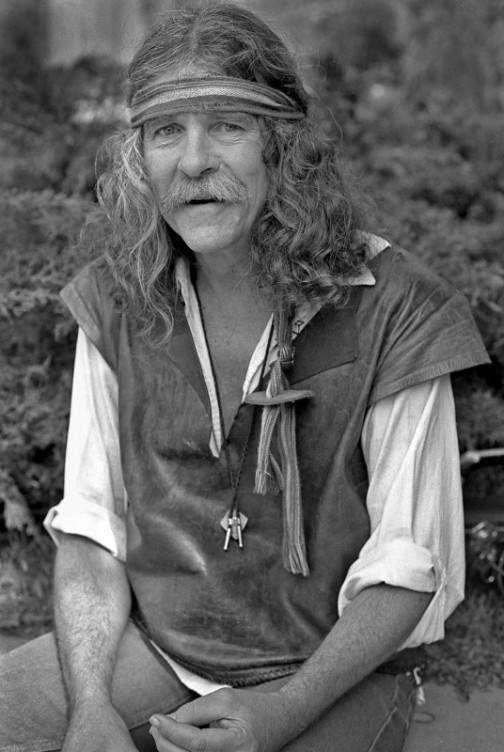

The closing prayer was offered by Ron’s nephew, Michael Thompson, whereupon the bodyless funeral cortege proceeded to the Provo City Cemetery. I stayed behind, lingering over a scrapbook of family snapshots that had been provided by Ron’s older sister, Shirlene. The pictures show the metamorphosis of a young American male, from Beaver Cleaver boyhood to Ollie North, the Vietnam years. In one picture Ron poses beside his first wife Barbara—the one he always referred to as “Barbie Doll.” After Barbie came Sylvia (hippie chick), who in turn was succeeded by Peggy (earth mother). All three are flat-out lookers! Clearly, Ron Booth had excellent taste in women—and, evidently, at one time the requisite social skills to win them over.

But as I turned the pages, I detected a gradual trend. Not necessarily upward or downward—but rather, outward. Yes, that’s it. Thanks to the miracle of time-lapse photography, I could see that from the day he came into this world on April 2, 1941, Ron Booth was steadily gravitating outward, moving farther and farther away from the center. Also, he was growing increasingly hirsute—so hairy that by the time his tenth high school reunion rolled around, his former classmates would scarcely have recognized him. That is, if Ron had bothered to attend.

By the time I got to the cemetery, the graveside ceremony had concluded and the funeral party had dispersed. The spot where Ron Booth’s remains, when located, will be laid to rest is but a few feet from the grave of Philo T. Farnsworth, “Father of Television.” Four folding chairs had been arranged in an arc facing a carpet woven of green synthetic material; underneath the carpet lay a sheet of three-quarter inch plywood. Curious, I lifted up the carpet and plywood and peered underneath, but all I could see was just an empty hole in the ground. It was then I recalled the somber words of Ron’s cousin Bob, the Mormon bishop: “It’s my belief that Ronnie has moved into the next phase of his eternal progression.”

On Saturday, six days following the funeral, I found myself standing in Salt Lake City’s Memory Grove, where a memorial service in Ron Booth’s honor was slated to commence at 4:30 in the afternoon. Counting myself, only five people had showed up.

“It’s just typical,” groused Richard Goldberger. “It’s all messed up and disorganized, just the same as Ron’s life always was.”

Richard Goldberger and Ron Booth had shared a long and often turbulent association dating back to the late 1960s, when the hippie movement was in full flower. More recently, Ron had accused Richard of becoming “too materialistic.” Yet it was to Richard’s door Ron would return time and again like a homing pigeon whenever he was in need of a few bucks to buy food, a bottle of beer, a package of cigarettes. Or two hundred dollars to bail himself out of jail.

John Russell nodded knowingly. John and Ron also go way back, having first met in 1969 over sandwiches at the Pinecone Restaurant on Main Street. In those days, John remembers that Ron wore John Lennon-style eyeglasses and had long hair that hung to his shoulders. In other words, he looked exactly like all the other campus radicals who hung out at The Huddle, who tossed Frisbees in Reservoir Park, and who discussed the works of Richard Brautigan while making free love amid pungent clouds of marijuana smoke inside funky psychedelic warrens all up and down Alameda Avenue.

No question about it, it was an interesting time to be young and alive. And right in the middle of the action was “Sergeant” Ronald Booth–arguably the sexual revolution’s most enthusiastic volunteer.

But times change. Russell was graduated from law school, got a haircut, landed a decent job. Ron Booth’s trajectory, meantime, continued outward. In the summer of 1972 he journeyed to Granby, Colorado, site of the first ever Rainbow Family Gathering. There he fell under the spell of a pudgy thirteen-year-old kid who billed himself as Guru Maharaji.

“And we were all there, of course,” recalled Robert Macri–another of Ron’s hippie-attorney pals. “Charlie Brown, John Holman, Boswell, Ron Booth—they all just felt that Guru Maharaji was it! That he was, in fact, Krishna.”

High on transcendental medication, the guru’s eager disciples promptly set about establishing the so-called Divine Light Mission, with headquarters in the Marmalade Hill district and later on G Street in the Avenues. Nobody knew for sure just what went on at the mission, but every so often they’d close up shop and set off on a religious pilgrimage to Guru Maharaji’s headquarters in the Far East—specifically, Florida.

“That was about all they did, is make pilgrimages,” Macri continued. “None of them had jobs, because every six months, or every three months, they had to make a pilgrimage. That was the most pilgrimagy group I’ve ever seen.”

When he wasn’t crisscrossing the country in his beat-up Pinto, Ron worked sporadically as a drywall finisher and plasterer. His clients included a number of prominent Utahns, including the painter Arnold Friberg. People he worked for complained he’d take five days to accomplish a task the average worker could finish in one. But he always did good work, and was meticulous to a fault.

He was also restless, and like a bird tended to migrate according to the seasons—south to Arizona for the winter, then north again to Aspen, Colorado, where for a time he worked as a cook at the Jerome Hotel.

But Ron could never be content for long slaving over a hot stove, for he was at heart an outdoorsman, a nature lover, and a fitness freak—long before physical exercise became popular.

“He was a very healthy fellow,” recalled Bob Macri. “And he loved to run. But he loved to run naked, and he loved to run early in the morning. And one morning he misjudged the time, and he was running down Seventh East when the sun came out.”

The cop who responded to a citizen’s complaint of a naked man running wild through the streets was far from gentle in making the arrest, added Macri. “Poor Ron ended up with black and blue marks from one end of his body to the other.

In years to come, the six-foot-two former paratrooper would suffer additional blows—some to the body, some to the brain, others to the heart. There was the fall from a ladder that landed him in the hospital with a head injury. There was a bout with pneumonia, and then a traumatic eviction from his tiny apartment on Second South—the place Ron always referred to as his “sanctuary.” The landlord then disposed of Ron’s possessions, including his Army uniform and a tape recording made at his father’s funeral. Thereafter, Ron Booth’s “home” became a cramped camper shell on the bed of his Chevy pickup. With no electricity and no heat, nights were terribly long and cold. And because he had no fixed address, concerned family members had a hard time keeping track of him. Nonetheless, the son Ron hadn’t laid eyes on in thirty years somehow managed to catch up with him.

“And Ron was so happy,” said Bob Macri. “But the main reason the kid had tracked his father down was to berate him and condemn him. And all he would do was show up at Ron’s truck at four in the morning, drunk and screaming, `You sonofabitch! You were never a father to me, you rotten sonofabitch!’”

Clearly, the good times were becoming increasingly few and farther between for Ron Booth. Perhaps the last occurred on a bright sunny Sunday afternoon in April of 1991, when a large crowd of middle-aged hipsters gathered in Memorial Grove to mark the passing of Utah’s most famous counterculture figure—Charlie Brown Artman. Ron showed up in full hippie attire, and a photo that appeared in the Salt Lake Tribune the following morning shows him locked in an enthusiastic embrace with an attractive, long-haired young woman. Not since 1975, the last year love could still be had for free, had Ron Booth been so happy.

The big difference between Ron Booth and the other attendees, however, was that after the party ended that evening, Ron had no home to return to. No place to go except into the foliage.

“We always took him for granted,” lamented Richard Goldberger. “He wasn’t recognized. He needed recognition, but somehow he fell through the hole of the Swiss cheese of his social fabric. He fell into the hole, and when you’re in the hole, you’re in the hole.”

Ron was now spending most of his daytime hours in the foothills above City Creek. At a natural hot spring north of Victory Road he could be found (had anyone been looking) soaking his weary bones in a thermally heated hot tub. Or else he’d be busy cutting underbrush and rearranging the rocks at his City Creek Canyon hideaway. Come sundown, he’d emerge like a bat from its cave and flutter about the city in search of sustenance. Homeless and all but friendless now, he counted himself lucky if he could score a bottle of booze and maybe find a parking space for the night.

In the morning, he’d appear at the Chevron gas station on Seventh East to buy a cup of coffee and use the restroom. Then one day, the station’s owner confronted him and insisted he leave. A scuffle ensued, and once again Ron ended up bruised and bleeding on the hard, cold ground.

“And I think that was what ended up killing Ron,” said Robert Macri. “He was so depressed by that. He just thought, you know, that he had hit rock bottom.”

“Physically he was still together, even though he was living on the streets or in his camper,” added Richard Goldberger. “But he was bleeding emotionally. He was estranged from his family, estranged from his kids. He was hemorrhaging emotionally.”

Ron picked himself up and vented his anger in classic Carson McCuller fashion: with his bare hands he ripped the emblem off a Trailways bus. It was a property crime for which he could have ended up behind bars had not Judge Dennis Fuchs decided to temper justice with mercy. Judge Fuchs encouraged Ron to check himself into the VA hospital for evaluation—and in lieu of a fine, ordered him to perform a hundred hours of community service. Since Ron was already spending most of his waking hours making various “improvements” along City Creek, in effect the judge was saying: `Carry on, Ron.’

For a time it appeared that Ron Booth might actually be on the verge of putting his life back together. Fate, unfortunately, had other plans. Early in 1998 Ron was diagnosed with a rare and incurable form of cancer; his final days were passed in a Provo nursing home, surrounded by patients much older than himself and light-years removed from those dimly-remembered glory days of the Nineteen Sixties.

“About Ron, there was always this desire to be an outrider, a want to strike out in a new direction.” said lifelong friend and former army buddy Paul Gammon. “But at the same time, he was wrestling with all of these things all through the years of trying in his own way to deal with those demons of rigidity. And then once he got outside of that rigidity, he ended up hurting himself really badly. But there was always a keen mind at work there, and he wasn’t just wandering around a blithering idiot. He wasn’t just a dirt bag who had fallen off a truck. He had a keen mind and there was a method to his meanderings.”

When it came my turn to speak, I confessed that I hardly knew Ron Booth at all. He was just someone I’d see now and again on the street, and once I remember I gave him a ride home from a party. Ron was drunk and had one arm in a cast, and we hadn’t gone far before he asked to be let out of the car because the night was still young and in his heart he just knew there must be a party going on, somewhere out there in the Stygian darkness.

But now the party had come to an end. Likewise, the sparsely-attended testimonial meeting in the park. But since it wasn’t yet dark, I decided to take a hike up the canyon and have a look at the community service project that had occupied so much of Ron’s last days on earth. What I found surprised me—a safety rail fashioned entirely of deadwood, running the length of a narrow passageway carved into the face of a cliff. Several feet below, City Creek tumbles and splashes over rocks that would make for a very hard landing were one to lose one’s footing. However, thanks to Ron’s railing, it’s unlikely anyone will ever slip and fall into the drink.

I ran my hands over the smooth, weather-worn wood and marveled at the primitive, yet solid craftsmanship. And the beauty! Without a doubt, it is a thing of beauty and a labor born of love. And now that winter’s here and my own days are growing shorter, I’m beginning to think there may be even more to Ron’s Railing than meets the eye.