Whenever people ask me why I haven’t moved away from Utah—perhaps to someplace better suited to my “liberal” temperament—I tell them it’s because I once had the rare privilege of having a thousand acres of the West all to myself. And beyond that familiar thousand acres lay thousands and thousands more acres that I had yet to foot on. Just knowing it was there—and STILL is—that’s what comforts me whenever I find myself sandwiched between a baby stroller and a missionary at Baskin-Robbins.

Last week I saddled up Yellow Peril and set off on a journey into the backcountry of my youth. Because skies were dark and threatening, I stuck mostly on the pavement, but then nature called and I couldn’t resist taking a chance on a dirt road marked “impassible when wet.” But, what the heck? I’ve been stranded out there before, and I always lived to tell about it.

The first time was back in 1962, if I remember right. I’d set out to explore Black Dragon Canyon with a girlfriend named Christine, who was from Manchester, England. But along the way my ’56 Mercury got swallowed up by quicksand, and the two of us spent the remainder of the day hiking back to State Route 24. It was dusk by the time we got there—just in time to hail a car occupied by an elderly couple from Hanksville.

“So where’d you folks come from?” asked the driver.

“Eng-a-land,” answered the footsore, sunburnt, and thoroughly dehydrated Christine—who, not long afterward, returned to Manchester. Clearly, the desert isn’t everyone’s cup of tea.

Dinosaur tracks and pictographs tell of prehistoric and pre-Columbian inhabitants, and once upon a time I could have led you to an inscription scrawled on sandstone by Matt Warner, bank robber, gunslinger and onetime cohort of Butch Cassidy. I can’t seem to find it now; either my memory is failing, or else the inscription been erased by erosion. In my hometown of Price, Warner was something of a folk hero, having served as town marshal following a period of “rehabilitation” at the Utah State Prison. In a WPA-era mural painted by local artist Lynn Fausett—on display at city hall—Warner can be seen holding court among a group of colorful cowhands. From what I’ve heard, he was a most congenial fellow!

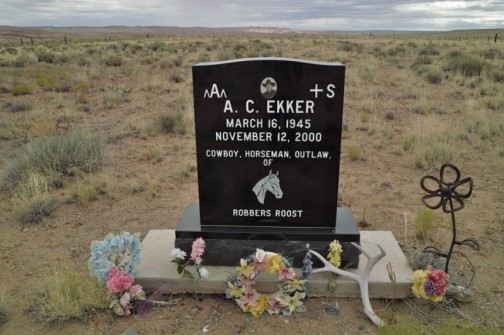

Indeed, as one gets deeper into Canyonlands, the terms “outlaw” and “cowboy” become pretty much interchangeable. I’m thinking in particular of the late A.C. Ekker, who—according to the inscription on his tombstone in Hanksville—was not just a cowboy and a horseman, but also an outlaw.

As far as I know, Ekker was a law-abiding citizen, inasmuch as there was ever such a thing on the remote ranch where he came of age. Known as Robbers Roost, it was the perfect hideout for fugitives looking to elude a posse.

“Not only is it remote,” Ekker once told me, “but when you get there and you look around the country—now, I wouldn’t wanna be chasin’ somebody in there. Because you don’t know which corner a guy might be around. So I think that it lent itself extremely well to the posse lookin’ around and sayin,’ ‘Well, I believe self-preservation is a little more important than catchin’ this guy, so we’ll go back to Castle Dale or Moab.’”

The only hard and fast rule at Robbers Roost is that you don’t go sticking your nose into anyone else’s business. I learned this when A.C. was showing me around his old family homestead and introduced me to the caretaker, a man Ekker referred to as “my pet hippie.” He seemed like a nice enough guy; however, no sooner had I unholstered my camera than he made himself scarce.

A.C. was less camera-shy, which is how I know he wasn’t on the FBI’s most-wanted list. In fact, his face had appeared on the cover of National Geographic Magazine. He’d also been written up in Sports Illustrated and Western Horseman. Named all-around intercollegiate national rodeo champion in 1967, A.C. was still competing in senior saddlebronc and roping competitions at the age of 55. I own the distinction of once having been caught between A.C.’s roping pony and a lassoed steer.

“Duck!” yelled A.C., and I did as I was told, losing a camera that day but not, fortunately, my head.

Sad to say, A.C. died only months afterward, of injuries sustained in a private airplane crash. A tombstone with his name on it stands in Hanksville, but he is elsewhere, his ashes now one with the wild, untamed country he knew and loved so well.