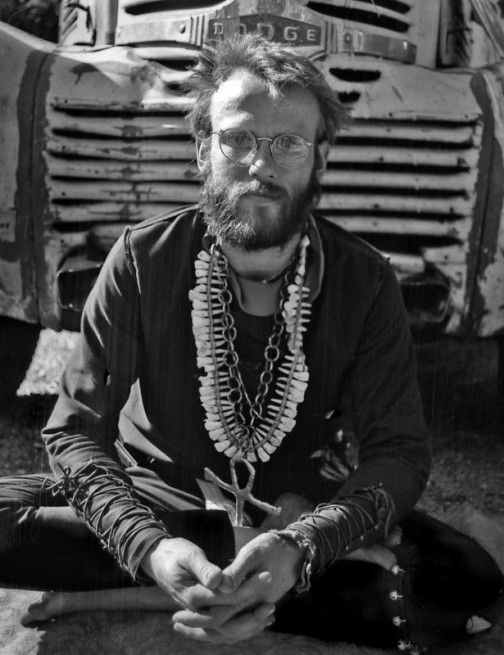

I may be the ONLY person of my generation who has never smoked marijuana. Which is strange, considering the fact I was well acquainted with just about everyone in the counter culture movement back in the Nineteen Sixties. And by everyone, I mean all six members of Salt Lake City’s hippie community—including the colorful Charlie “Brown” Artman, founder of the so-called Alameda Street Church, where services included a peace pipe ceremony and other forms of transcendental medication.

I wasn’t a member of the congregation, although at the time I remember wishing I could afford to rent an apartment on Alameda Street, where in every loft lived a bookish fellow named John and his earth mother woman Suzanne, who wore a paisley print caftan dress and served up tea and oranges that came all the way from China. Alas, the best I could do was a basement apartment on Apricot Avenue, in a rundown section of town known as the Marmalade District. My neighbors included two ex-cons, an alcoholic recluse and a crazy woman named Diane. From time to time Charlie Brown Artman’s psychedelic school bus could be seen parked in Diane’s driveway. At other times, when he wasn’t in jail on one charge or another, Charlie could be found running barefoot in Reservoir Park, his black cape and hand-forged brass ankh flapping in the wind. I knew Charlie mostly through his attorney Bob Macri, who once offered me a joint—which I tried to smoke but couldn’t, because I was a non-smoker who (like Bill Clinton) had never learned how to inhale. I was such a straight arrow, I have no idea what I was doing surrounded by druggies. I’m guessing every trip requires a non-tripper, someone to serve as a baseline so that the trippers can take one look at him and judge just how “far out” they’ve ventured.

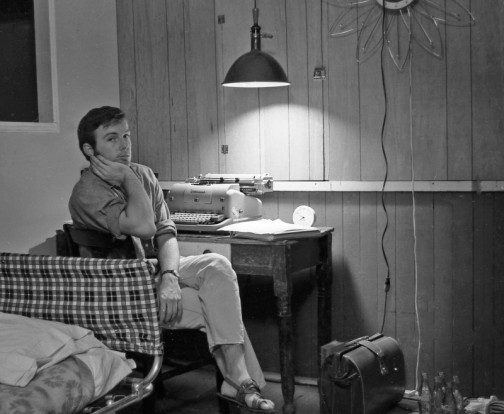

So I never smoked pot; however, In Texas I once became a speed freak—entirely by accident. I was working at the time at a photography studio in San Marcos, pulling down fifty bucks a week, plus lodging in a wood-paneled garret above the darkroom. Nighttimes I would peck away at my electric Underwood in hopes of one day selling something to a magazine. It was challenging work, and I’d often sit for hours staring at the keyboard, not knowing where to start. Then one day I turned to Beatrice, one of the girls who worked at the studio. Beatrice was an amazing worker; in half an hour she could accomplish more than I could in a week. “What is the secret of all your energy?” I asked.

“Diet pills,” she answered. “Not only do they kill your appetite, they help you get started on whatever it is you need to do.”

Beatrice volunteered to get me some diet pills—and, amazingly, her pharmacist was happy to oblige. The very next day I had entire bottle in hand.

“Wash one down with a Coke,” Beatrice suggested. “You’ll be up and at it in no time!”

Wow, she wasn’t kidding. Early the next morning, about four a.m., I had finished typing a letter to a person barely knew. What was it about? About forty single-spaced pages!

Thanks to Beatrice’s diet pills, I no longer had any trouble with blank pages. Only trouble was finding enough paper to accommodate my amazing output of long letters to people I barely knew and also articles to various magazines, which—like my imaginary pen pals—never responded. Then one day a miracle happened: Reader’s Digest sent me a check for two hundred dollars, for an anecdote that measured a mere two paragraphs. I did the math: An amount equal to an entire month’s pay, for a mere 98 words!

The very next day I quit my job and moved up the road to Austin, where a girl I knew was working toward her master’s degree. Naturally, she was impressed to learn I was a published author—impressed enough to let me move in with her.

Life was good! Austin in 1969 was a major hippie enclave, and there I was living high on my royalty check and being waited on by an auburn-haired beauty. Thanks to those diet pills, I no longer suffered from writer’s block. Getting started was no problem; the problem was knowing when to stop.

“Why don’t you knock out another paragraph for The Reader’s Digest?” asked Anne. “We’re, like, running low on tea and oranges.”

“Problem is,” I answered, “I can’t seem to write anything shorter than 25,000 words.”

By and by it came time for Anne to turn in her master’s thesis. Thanks to me, she had uncharacteristically been putting it off, and of course I felt guilty about that. So I told her we’d trade places; I’d take a turn at serving up the tea and oranges that come all the way from China and she could be the writer-in-residence. She could have the use of my electric Underwood and what remained of Beatrice’s magic diet pills.

“Wash a couple down with a Coke,” I said. “You’ll be up and at it in no time.”

That night the apartment rattled with the staccato tap tap tapping of typewriter keys. Come dawn, voila!—the Underwood was a smoking ruin but the thesis was finished! Was it any good? Who knows? The good thing is, Anne got her master’s degree and as a result was able to find a good job in order to support a husband who through all these many years since has yet to sell another word to the Reader’s Digest.