My father was the kindest, gentlest, most even-tempered man who ever lived. Even so, there’s a limit to just how much aggravation a man can put up with. I’m thinking of the time my brother and I threw away Dad’s Whirlaway.

So, what’s a Whirlaway? You might rightly identify Whirlaway as the name of a famous racing horse, winner of the Triple Crown in 1941. However, my father was a man of modest means who never owned an expensive racehorse—lucky for him, I suppose. What he did own, very briefly, was a combination rod and spinning reel that came onto the market in 1953. Coiled inside the bulbous butt end was a hundred yards of monofilament line, enough to cast a plug smack dab in the middle of the lake where surely the biggest trout lurked.

My father had received his Whirlaway as a present from my mother on the occasion of his forty-second birthday. The purchase price—a figure that lives on in infamy—was a whopping $24.95

Dad’s birthday came in early February, almost four months prior to opening day of fishing season, so for all that time the gleaming Whiraway had been sitting in his closet but not gathering much dust, because almost every day after he came home from work he’d take it out and caress its baroque curves, fiddle with the crank and sight down its virgin ferules.

Warm weather came at last, and with it snowdrifts blocking roads into the high country began to melt away. Aspens leafed out and shimmered in the sunlight; wildflowers burst into bloom. Then came June first. Time to take the Whirlaway out of the closet.

My parents belonged to a social group known simply as “The Club.” Mostly it was a ladies club; however, at least once a year husbands, wives and children would congregate at a campground high atop the Wasatch Plateau. On this particular overnight outing the destination was Ferron Reservoir, a lovely body of water rimmed by groves of luminous aspen trees. Presently the station wagons were circled up, tents pitched, and campfire lit. Men gathered wood; womenfolk set about unpacking wicker baskets filled with groceries and pink and tudrquoise melamine dinnerware.

In the meantime, my older brother Chuck and I were already on the water, rowing a boat someone had thoughtlessly left unattended at the dock. More precisely, I was doing the rowing while Chuck sat astern and barked orders. Clutched firmly in his freckled paws was our father’s brand new Whirlaway!

“Hey, Chuck,” I said. “I don’t know if this is such a good idea. After all, this isn’t our boat, and I don’t remember asking Dad if we could borrow his Whirlaway. I mean, he hasn’t even had a chance to use it himself yet.”

“Shut up and row,” my brother growled, bending to tie on a silver gray J.C. Higgins flatfish that he had “borrowed” from Garth Frandsen’s tackle box. “I’m gonna troll this sucker and you just wait and see. We’re gonna catch the biggest trout there ever was.”

“Chuck, are you sure…?”

“I said, ‘Shut up and row! How can I troll if the boat ain’t movin’?”

I kept rowing, but it was hard work, and for some reason the boat kept wanting to turn in circles. And the harder I tried, the testier my brother became. I began to wish he had “borrowed” an outboard motor instead of his little brother for this fishing excursion.

“Jeez, can’t you do anything right?” Chuck sighed wearily, set down the Whirlaway and made his way amidships. “Here, gimme them oars! I guess I’m gonna have to teach ya how to row a boat.”

At that precise moment a sharp “twang” rent the still mountain air as our fishing line was suddenly drawn taut. Mouths agape, we stared transfixed as the rod tip bowed sharply. Then boing! Over the stern went the Whirlaway! The action probably lasted only two or three seconds, but in my mind’s eye it seemed to go on forever–like a slow-motion Sam Peckinpah shoot-out.

Falling over one another, we scrambled to the rear of the boat just in time to watch in horror as the silvery ghostlike form of our father’s brand new spinning reel disappeared forever into the mossy green depths. A moment later we heard a distant splash. Looking up, we saw what was, indeed, the biggest trout there ever was. For the longest time it seemed to hover in the air, Garth Frandsen’s J.C. Higgins silver gray flatfish dangling from its lower jaw. Then with a great ker-plop, Moby Trout disappeared beneath the surface, never to rise again.

For the longest time we two sat frozen in mute despair, staring into the opaque water and hoping against hope for some ray of light to pierce the deepening gloom.

“Richie…Chuckie!” From far away across the world we heard our names being called. Turning our dead gazes shoreward, we beheld a posse of adults waving and gesturing. Among the crowd we could make out the faces of the rightful owners of the rowboat, the flatfish–and, dear God, the Whirlaway!

It happened that I didn’t die that day, although I was confined to camp for the remainder of the afternoon and sent to my sleeping bag that night without my pork & beans. My brother’s punishment was equally harsh. However, if anyone truly suffered that day, surely it was my poor father. When it came time for the other husbands to take up their poles and go forth to fish, my father didn’t join them. He just sat by the campfire, staring forlornly into the ashes.

But as someone once said, no experience is a total loss provided you learn something from it. Years afterward, when a college professor inquired if anyone in the class knew the meaning of the word “pathos,” mine was the first hand up.

So I had lost one fishing pole but increased my vocabulary, and in time I came to believe my father had forgotten the whole ugly incident. I suspected as much because over the course of twenty years no one living under our roof had ever once uttered the word, “Whirlaway.”

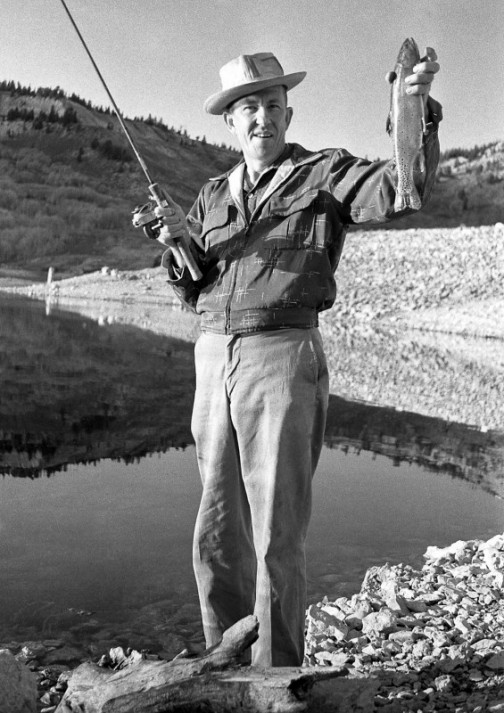

In the meantime I had grown to maturity, old enough now to talk to my father as one adult to another. From time to time the two of us would go fishing together, and so it came to pass one fine autumn day we found ourselves casting our lures into the placid waters of Ferron Reservoir.

Presently my father hooked onto what what at first he thought might be a fish but which turned out to be an old fishing line.

“Seems to be attached to something heavy,” Dad declared, as he began hauling in the snag hand over hand.

There ensued a most pregnant silence. I attempted to say something, but all I could do was silently move my lips.

Dad didn’t say anything either. He just kept hauling in that line, and with each pull the suspense mounted. Tidal waves of long suppressed emotions—guilt, fear, regret, anguish—washed over me. At any second I fully expected to see the barnacled hulk of the long lost Whirlaway emerge, along with the skeletal remains of the titanic trout.

At last the prize surfaced, and, lo and behold, it was a fishing rod and reel! Alas, it wasn’t the Whirlaway of yesteryear. As I recall, it was a Shakespeare, or maybe it was a Zebco. But then what does it matter?

“Hmmm…” I said. “Now how do you suppose that thing ended up in the lake?”

“Probably,” my father answered evenly, “some knucklehead kid put it there.”