In Utah, it’s possible to purchase an alcoholic drink in some restaurants but not possible to watch as one’s cocktail is being mixed—the idea being that if children were to catch a glimpse of the process they would immediately want one. So state law requires that a seven-foot, two-inch tall barrier be erected between the onlooker and the bartender—the so-called “Zion curtain.” But wait! It gets even stranger. Before the patron can have his drink, he must first present a photo I.D. and answer this question: “Do you intend to also order food?”

So first you order the meal and then no peeking behind the curtain as your cocktail is being prepared. It’s pretty much the same protocol as death by lethal injection at the state prison!

Having grown up in Utah, there is a part of me that still wants to close the drapes whenever I pour myself a drink. My doctor has diagnosed my condition as “neurosis of the liver” and suggests the best remedy is to spend more time drinking in places where there is no barrier separating the barkeep from the barfly. Places such as Nevada, for instance, where the bartender is much more than just someone who mixes drinks. He (or she) is a confidante, a psychiatrist, social worker, life coach, matchmaker, friend—or maybe just someone who’s a lot more interesting than whatever is playing on the television above the bar.

I’ve written before of Miguel Olano, owner and for many years a fixture at the Winnemucca Hotel. Mike’s specialty was the Picon Punch, a potent aperitif one consumes while waiting to be seated in the dining hall. Consume more than one and you won’t mind the wait. Down three and you won’t recognize your name when finally it is called.

Basques drink a lot but never get falling down drunk. The more they drink, the more heavy stuff they can lift, and it’s not unusual to see a Basque leaving a bar with his pickup truck on his back rather than risk getting a citation for driving under the influence.

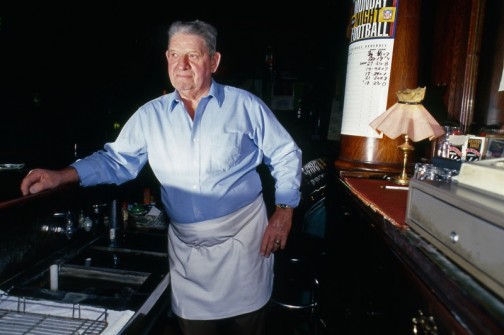

Another of my favorite bars is the McGill Club in McGill, where for seventy-some years Norm Linnell poured drinks, taking only one sabbatical back in the Nineteen Forties in order to fight the Japanese in Burma. The night Norm’s red Dodge pickup went missing, people began wondering if perhaps a Basque had picked it up by mistake. Then again, maybe it was Marco “Buddy” Yukich from nearby Ely.

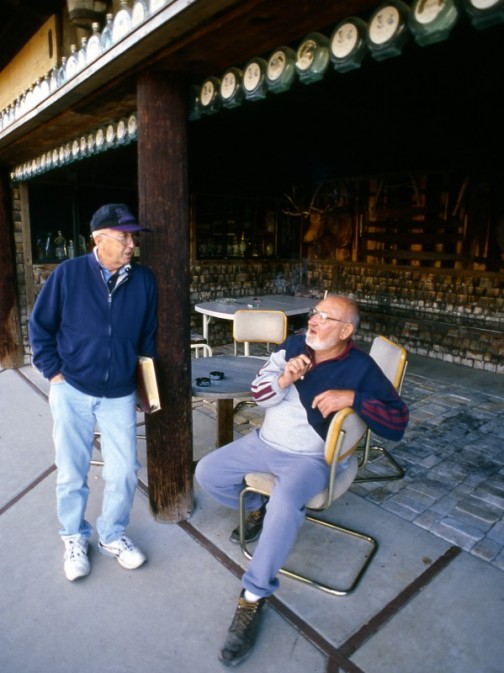

“We taught the Basques to drink,” declared Buddy, whose forebears emigrated from Yugoslavia. We were seated at a table inside Buddy’s entertainment compound named Slivo Street—after the proprietor’s favorite alcoholic beverage Slivowitz. Hundreds of empty Slivowitz bottles lined the driveway and ringed the backyard enclosure, which included a smokehouse, a walk-in cooler, three barbecue pits and a private saloon, the Antler Club.

Joining us was Buddy’s longtime pal Ed Lemmich from Ruth. Ed’s forebears were Croats; Buddy’s were Serbs, but there was never any animosity between them. Their main concern during the Bosnian war was that an airplane might accidentally drop a bomb on a plum orchard, plum juice being the base ingredient of Slivowitz.

I had never tasted Slivowitz before, let alone downed a mason jar full—so I don’t remember much else about that interview, and my field notes are illegible. Still, I think I learned something. When it comes to bringing people of differing backgrounds together, an open bar is infinitely preferable to a partition. So maybe it’s high time we in Utah tore ours down and became better acquainted with whoever’s on the other side.