Forty some years ago I was poking around the quaint little farming village of Fountain Green and came upon an abandoned shack—known locally as “the old photographer’s house.” On the porch I discovered two or three boxes of Taprell & Loomis photo cards, an unopened package of Seed’s dry plates, a 5×7-inch contact print frame and a little cardboard box containing what I presumed was long-expired printing paper. I decided to grab the stuff and make a run for it, a caper that was evidently captured by a security camera. Lucky for me, said security camera used Kodak Verichrome Pan film, and so by the time the prints came back from Walgreen’s, I was long gone.

Should I feel bad? Well, no. Had I not rescued the stuff, it would have long since ended up in the landfill Why? Because no one at the time realized that the “old photographer” was Utah’s foremost chronicler of pioneer life George Edward Anderson, whose work has only recently become widely known and much admired. That’s just how it goes, isn’t it? In the words of Joni Mitchell, “You don’t know what you’ve got til it’s gone.”

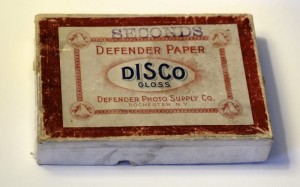

Even I didn’t know exactly what I had—not until I finally got around to opening the photographic paper box. What I found inside were negatives, all marked “seconds.” And that’s when I knew for sure the work was Anderson’s, because only a true artist could find fault with those negatives. Some of the images are from a trip the photographer took—a transatlantic voyage to what looks to be Denmark and Holland. Along the way he also traveled on a riverboat—a steam packet named Greenwood that plied the Ohio River between 1898 and 1925.

Here are two images from that trip: one, showing finely-dressed passengers awaiting departure at the dock.

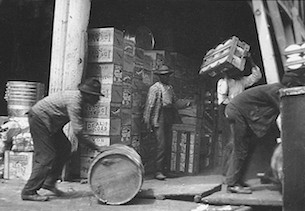

And then this one, showing dock workers lading cargo in the lower deck. Then, as now, social stratification was the American way.

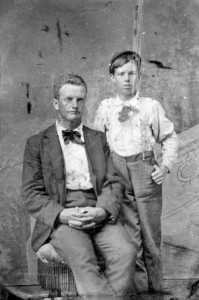

What’s amazing is that a moment in time captured over a century ago can still be brought to life. I can print a black and white negative or a glass plate in my darkroom, or I can just toss it onto my Epson flatbed scanner. Heck, I can even scan a tintype, such as this one of my grandfather John Wesley Morton (seated, left) , and lo and behold! It comes out even better than it did in 1898.

It all makes me wonder: will the pictures we’re taking today be around a century from now? Will the technology required to recover them be available? Given the fact the digital camera I bought just five years ago is already obsolete, I doubt it. Which means those unsung photographic geniuses who labor anonymously among us today will most like remain just that. Anonymous, unsung, dead and gone as the subjects they photographed.