Once, when I was very poor, I went to the Utah State Fair just to make money. They were running a contest to find “the best picture taken at the state fair,” and I figured that blue ribbon had my name on it. Armed with my old Exakta camera that was held together with electrician’s tape, I stalked the midway in search of the decisive moment. Over the course of an hour I shot thirty frames, one of which was deemed the winner. The prize was 25 dollars.

Twenty years later (1988) I was sitting in my darkroom when the telephone rang. It was the state fair again. On the eve of opening day, their official photographer had just called in sick. Would I consider standing in for him? The pay would be a hundred times what I had earned last time I attended the fair. The catch? I’d have to stick around for longer than an hour.

Next thing I knew, I was perched on the grandstand bleachers, watching as an endless parade of young ladies known as “county queens” competed for the coveted title of “state fair queen.” Compared to those governing the selection of official fair photographer, the rules were pretty strict. Each contestant had to “be single and never have been married nor had her marriage annulled nor may she have co-habited with a male in lieu of a marriage contract, and must not be and never have been pregnant.” Moreover, contestants had to be “of good moral character and shall not have been convicted of any crimes.”

The competition is particularly hard for young girls from the boondocks who must compete with relatively sophisticated city girls. For example, useful agrarian skills such as weight lifting and steer wrestling don’t rock the house the way they did back in Panguitch. So I knew right away that Miss Salt Lake County would win the title. She could sing, she could dance, she could play the piano, and she was an expert on U.S. foreign policy. Best of all, she was taller than her three attendants—or maybe she just had taller hair.

Over the course of the next ten days I would gain a great deal of admiration for these young ladies. Like me, they were required to be on call every day until the fair closed. Unlike me, they had to keep smiling the entire time.

Mornings began in the horticultural building, where exhibitors could be found arranging their apples and polishing their pumpkins. There I met a Mr. Higby of Grantsville, who spends his summers cultivating gourds of various shapes and colors—not two alike. Farmer Higby and his wife—along with countless other farmers and farmers’ wives—are what we in the Beehive State call worker bees. They spend their days toiling in fields, workshops and kitchens, their goal to produce the perfect pumpkin, the faultless jar of grape jelly, the peerless pig, the prettiest and most talented daughter who has never been pregnant nor convicted of any crimes.

That afternoon I spent photographing chickens and rabbits. Come sundown, it was off to the grandstand to take a picture of Eddie Rabbitt. But even as the band began to warm up, I was still without a press pass—the bureaucratic explanation being that I wasn’t this guy Kelly who had had been awarded the contract but who had called in sick. No amount of pleading on my part was going to get me past the gate, so when it came show time, I had to buy myself a ticket.

Stealthily, I worked my way toward the stage, hoping to keep a low profile. I was only vaguely familiar with Mr. Rabbitt’s music, but with a name like that, I assumed it appropriate that I should try to sneak up on him. But no sooner had Eddie taken the stage than a frenzied mob of female fans packing Instamatics bolted from their seats and rushed forward. Rabbitt didn’t run but held his ground, squinting against the glare of exploding flashcubes while singing, “I love a rainy night…I love a rainy night…”

Actually, it was raining girls. A tsunami of squealing, squirming, frothing-at-the-mouth females washed down the aisle and I became a helpless piece of flotsam. Just as I was about to go under, I felt myself being pulled from the melee. Then came a voice with a strange but familiar Russian accent.

“You’re not Kelly?”

I’d just been rescued by a Utah institution, the irrepressible impresario Eugene Jelesnik. Host of KSL television’s long-running Talent Showcase. Jelesnik was Utah’s very own Ed Sullivan—and here we were locked in an intimate embrace.

“I’m not Kelly,” I introduced myself. “He called in sick. I’m filling in for him.”

Eugene pulled me aside and sat me down. Then for the first time since I took on the assignment, the precise function of official state fair photographer was spelled out for me. My job was to be loaded and ready to fire whenever Eugene came within grabbing distance of a visiting show business celebrity. So forget about the pumpkins, forget about the chickens, and forget about the pigs—that is, until tomorrow’s livestock judging.

Livestock! Taking pictures of farm animals is surprisingly difficult; in fact, I’m told there are photographers who specialize in it. Moreover, there are judges who can tell the difference between one sheep and the next, even though to me they all look pretty much the same. It’s not about composition; it’s all about “configuration.” It might take as many as six people to arrange a Holstein milk cow, which in my viewfinder looks like a cow with twelve extra legs. And cows are easy compared to pigs, which are well nigh impossible subjects.

“Pigs,” explained livestock supervisor John Bleggi dryly, “don’t exactly pose on point.”

Bleggi was right. The only way to engage a pig’s interest is to introduce a bucket of slop into the picture. And here I shall refrain from adding the gratuitous comment regarding political fund raising banquets.

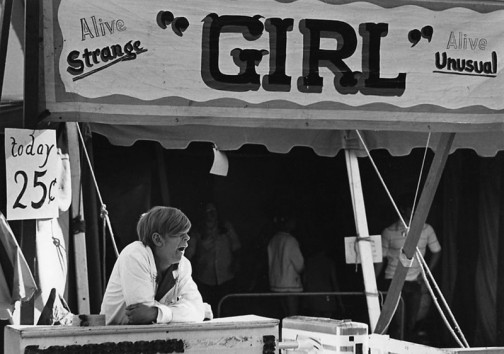

I was more than happy to escape into the relatively fresh air of the midway, where over the course of ten days I became acquainted with several carnies, among them a fellow named Ned Lewis, who had a monkey named Buddy. Periodically, Ned would lead his monkey around on a leash and right away he’d attract a following. As far as I could tell, Buddy had no special talent. The “act” consisted of Buddy cowering while Ned said, over and over, “Don’t touch the monkey, folks.”

Ned told me that he was one of just half a dozen organ grinders still operating in the country. How he knows that, I can’t say. I suppose there’s a publication called “Modern Organ Grinding” and they have only six subscribers.

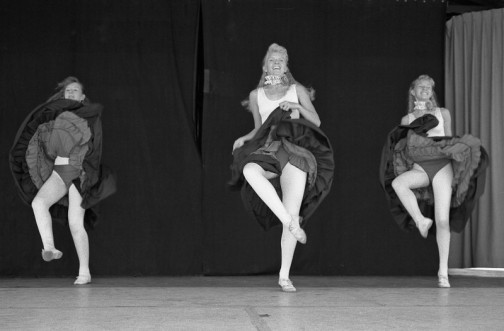

Other entertainments took place at half hour intervals throughout the day–everything including musical groups, cooking and sheep shearing demonstrations, magic acts, puppeteers and martial arts demonstrations. But mostly there were dance groups from West Valley, all stepping in sync (sort of) to the patriotic lyrics of country star Lee Greenwood.

“I’m proud to be an American, where at least I know I’m free…”

Easy to say for the Junior Jingoettes. They were free to go home after the performance. Me, I’d be a fixture on the fairgrounds for the remainder of the week. The longer I stayed, the more the state fair park began to feel like the state prison. I bought a coke and wandered over to sit beside the murky waters of the Jordan River. On the other side lay freedom; however, the bridge leading to the west gate was patrolled by sentries. I entertained the thought of swimming to freedom, perhaps using my soft drink straw as a breathing tube the way I’d seen it done in movies.

Night found me back at the grandstand, reprising my role as Eugene Jelesnik’s personal photographer. The target this time was country star Charlie Daniels, a regular sort of fellow offstage who graciously consented to pose next to the diminutive Jelesnik—the pair exchanging hats for comical effect.

Gene –we were now on a first name basis, he being “Gene” and I being “Not Kelly,” which I thought had a nice showbiz ring to it—Gene suggested I stick around for Charlie’s second performance of the evening, but I had orders to hustle myself back to the stockyards where an animal fashion show was getting underway. Yes, lambs in hats and neckties, goats in clown costumes, a sow dressed as Miss Piggy. Happily, no entrants were quizzed regarding U.S. foreign policy.

I was beginning to feel very sorry for myself, but of course I wasn’t the only one who was suffering. Take, for instance, the people who run the commercial booths and public service displays. Out behind the coliseum was a solitary soldier assigned to stand guard over some sort of esoteric military vehicle. Once in a great while someone would stop and ask him what the heck it was, whereupon he’d launch into a spiel about what a great life it is in today’s National Guard. A great life indeed!

The days now seemed to drag on forever. When would the damn fair end? I was beginning to feel as shriveled as the tomatoes in the horticultural hall, and a steady diet of corn dogs and funnel cakes was wreaking havoc on my digestive tract. I staggered weakly from one event to the next, snapping everything from lop rabbits to Tanya Tucker with equal indifference.

Then late one afternoon, as I lay on my back in the grass near the main entrance, gazing up at the sky and wishing I could fly, I heard the dulcet lyrics of Verdi’s “Ave Maria.” It was so beautiful that for a moment I imagined I had died and gone to heaven.

Gathering myself up, I staggered in the direction of the music. It was coming from the throat of a young man whose name, I later learned, was Robert Klose. Klose was standing all by himself next to the entrance to the Fine Arts Building, hands clasped, eyes, closed, singing his heart out. There was no one in the audience except myself, although from time to time a curious head would poke from inside the open doorway, then disappear.

At the conclusion of his performance, I burst into wild applause. I was surprised to find I had been moved to tears by the beauty of this voice crying in the wilderness.

Later, Klose joined me on the grass and together we compared notes on our experiences at the fair. He, too, had been having a hard time of it. Earlier in the day he’d been chased away from the midway by a carnival barker. He’d then relocated beside the Coliseum, only to find that his vocal cords were no match for lumberjacks wielding chairsaws. Finally, he’d become a roving troubadour.

As they say at the Utah State Fair, there’s something for everyone, and the fact it took me ten days to find something should in no way be taken as an indictment of the institution. If I’ve learned anything in this life, it’s that I’m probably not your typical state fairgoer. Which is why, following Lee Greenwood’s second set on the final night of the fair, I walked out the gate and during the 25 years since have never once returned. Greenwood is absolutely right: Freedom is a wonderful thing.