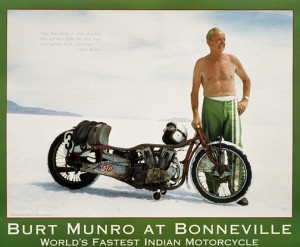

Joe Rosenthal took his big shot atop Mount Suribachi; Dorthea Lange hers in a migrant worker camp in Nipomo, California. Mine happened during Speed Week on the Bonneville Salt Flats of Western Utah, back in August, 1971. A little known, unheralded speed cyclist by the name of Burt Munro had just returned to the pit area following a 147-mph run through the measured mile. He climbed off his fifty-year-old bike, doffed his open face Bell helmet, peeled off his black leather jacket and stretched. For a man of seventy years, Mr. Munro looked to be in pretty good shape!

Mine was the only camera on the scene that day, and–like Burt–I was operating on a shoestring budget. I was armed with an Exa camera and just one roll of Kodachrome film. The Exa was the cheapest SLR one could buy; however, at the time it was attached to a pretty nice Steinheil Quinaron 35mm lens. I’ve always maintained that if you can’t afford to buy a good camera, then at least buy a good lens. Evidently the thief who one night broke into my Volkswagen bus was of the same opinion. He took the lens, but left me the camera!

Looking at it today, it’s hard to believe I could ever take a halfway decent picture with it, let alone one that I’ve sold thousands of times. Honestly, it’s the closest thing I have to an old age pension.

But money isn’t everything. What I treasure more are the letters I get from buyers scattered across the globe, from North Pole, Alaska, to some unpronounceable settlement in Western Australia. “Looks great next to me toolbox, mate!”

The poster also adorns the workshop of a Swede named Anders Johansson, who—like Burt—came of age in a village where “misfits” were treasured “since they often were the ones producing the best stories even though they didn’t always know about it. Unfortunately, most of our oddballs are between retirement and death by now and few are taking their place since the modern school forces even the strangest children to accept the norms of society.”

Anders most definitely doesn’t fit the norm. He is building—and I kid you not—a gas turbine powered motorbike with an estimated top speed of 300 miles per hour. And his dream, like Burt’s, is to someday make the pilgrimage to the holy land of maximum velocity: Bonneville.

Lately my Burt Munro poster has been popping up everywhere. Recently on television I caught a glimpse of it over the left shoulder of Las Vegas pawnbroker Rick Harrison, who was making his way to Sturgis.

I’m waiting for the episode of “Pawn Stars” where a customer brings in an autographed copy of the poster. A Speed Week enthusiast named Burton Brown of Fremont, Wisconsin, writes to say he spotted one of my posters on the wall of a Harley Davidson dealer, “and it appears to be signed by Burt.”

Quite a feat, since Burt died thirty years before the poster came out!

That said, I like to think that I, too, have had a hand, however small, in resurrecting New Zealand’s eccentric racing legend. If Burt were alive today, no doubt he’d be pleased to know that men of a certain age the world over are busy tinkering with their beloved machines and not fretting overmuch about what other people might think of their odd lifestyles and curious obsessions. And still dreaming of someday making it all the way to Bonneville, Utah.